There were ten in the bed: bedsharing pros and cons

Sleeping babies - who would have thought it to be such a contentious issue! While many frown upon bedsharing, Sarah Tennant has found that it best suits her family. What's more, research now suggests that sleeping with your baby is often not only safe, but mutually beneficial.

Being a first-time mother is hard. Not so much the mothering itself, but the running commentary. From the ever-popular "Why haven't you put a hat on that baby" to "Look at that chin, she must be teething", I have received enough unsolicited parenting advice in the last five months to run an orphanage.

Mostly the comments are harmless, but on one subject, the conversation can take a more ominous turn. My daughter Rowan sleeps in our bed, and I am swiftly learning not to mention that fact, because of what I'll inevitably hear: "I thought that wasn't encouraged these days." "Aren't you afraid you'll roll on her?" and "Is it safe?"

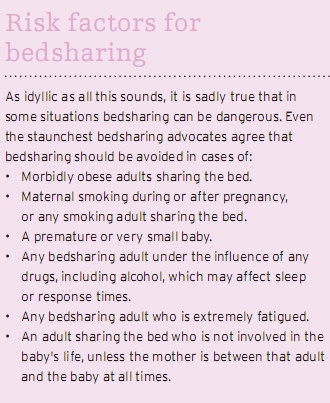

To be fair to my acquaintances, bedsharing is, indeed, heavily discouraged. Plunket nurses warn against it. Parenting experts like Dr Spock, Dr Ferber and Gary Ezzo condemn it. The USA tackled it in their "ABCs of Safe Sleep" campaign, claiming that a baby is safest "Alone, on his Back, in a Crib". Yet somehow, this message isn't getting through. Around the world, mothers are obstinately continuing to do what mothers have always done - sleep with their babies for warmth, comfort and easy breastfeeding. In 1995, it was estimated that 17% of three- to six-month old Kiwi infants routinely bed-shared. Not only that, increasing numbers of attachment-parenting advocates, sleep researchers, and psychologists are now speaking out in favour of bedsharing. So are we putting our babies at risk?

Mangled data

Perhaps the most influential piece of research on cosleeping is a 1999 study by the Consumer Products Safety Commission (CPSC). Used as a basis for several anti-cosleeping campaigns, the study has been heavily criticised for bias. The statistics, taken from infant death reports, did not contain sufficient demographic data to determine whether cosleeping posed a universal risk, or was only dangerous in specific situations. The results also failed to distinguish between unsafe cosleeping situations (such as an intoxicated parent, prone sleeping position, or maternal smoking) and minimal-risk bedsharing. In an article examining the laws of the CPSC study, Patricia Donohue-Carey notes that "the CPSC researchers did not frame the significance of this missing data, choosing instead to focus solely on the location of these children at the time of death".

Notably, despite these factors, the CPSC results actually come out in favour of cosleeping, when analysed against population data. Tina Kimmel calculates that the study shows it is "less than half (42%) as risky, or more than twice as safe, for an infant to be in an adult bed than in a crib".

Unfortunately, other studies demonstrate a similar bias towards considering bedsharing inherently risky. A New Zealand study examining the relationship between SIDS, bedsharing, and maternal smoking found that infants in nonsmoking homes were more likely to die of SIDS if they had bedshared in the last two weeks, but not during their final sleep. Rather than questioning whether those deaths could have been caused by the infants' not sleeping with their mothers as usual, the study concluded that "infant bed sharing is associated with a significantly raised risk of the sudden infant death syndrome, particularly among infants of mothers who smoke".

Ideological bias

Why would scientists be biased against bedsharing? Attachment-parenting advocates argue that the objections are ideological rather than scientific, reflecting a uniquely Western set of values. Whereas the rest of the world tends to view the mother-child relationship as primary, Western thought prioritises the relationship between husband and wife. Traits such as individuality and self-reliance are highly valued, and the need for privacy is stressed.

The results of this thinking are babies who are expected to behave like adults - falling asleep alone and waking again after an unbroken sleep. Infants who cry out for attention are labelled manipulative; mothers who wish to sleep with their babies are warned that they will create a clingy, dependent child.

Although these theories have now been debunked, the ideological climate that created them still lingers. Resultingly, it's not surprising that many experts consider bedsharing primitive or distasteful-but as medical anthropologist James McKenna points out, these are social judgments; not science.

In defence of bedsharing

Reading through anti-bedsharing websites, I was struck by how similar the arguments were to the anti-breastfeeding rhetoric of the 1950s. Once considered psychologically suspect, lower-class, and unscientific, breastfeeding has only recently regained respectability as science confirms what instinct has always known. Similarly, the benefits of bedsharing are beginning to be recognised.

At the forefront of bedsharing research is James McKenna, director of Notre-Dame's Mother-Baby Behavioral Sleep Laboratory. Studying hundreds of mother-baby pairs, McKenna found that mothers instinctively protect and nurture their infants, even during sleep. Most mothers curl up around their babies, knees drawn up, with one arm above the baby's head. This position allows for easy breastfeeding and prevents the baby from wriggling up and down the bed. It also makes overlying virtually impossible, as the mother's knees and arms form a protective shell around the baby.

The proximity of baby to breasts also encourages frequent feeding, a fact noted by La Leche League International. Bedsharing mothers tend to breastfeed for longer before wearning, which confers numerous health and immunological benefits to the baby. Bedsharing babies also feed more frequently; sometimes as often as every 90 minutes, as mother and baby simultaneously rouse during the light stage of the sleep cycle. These added feeds, along with increased skin-to-skin contact, are highly beneficial for infant weight gain.

But, most importantly, breastfeeding significantly reduces the risk of SIDS. Even just being close to a parent is now considered beneficial. Babies often suffer from apnoeas - temporary cessations in breathing - which can be dangerous. The parents' breathing provides a regular metronome, helping babies to regulate their own respiration. Similarly, frequent rousing by being in proximity to parents means less time spent in the deep stages of sleep, which have been implicated in SIDS. The mother's body also helps her baby regulate his temperature, further decreasing the SIDS risk.

Psychologically, too, bedsharing is now realised to be beneficial. Fresh out of the womb, babies crave the security of maternal heartbeat, scents and touch. In the light stages of sleep, mothers and babies instinctively "check in" with each other. Dr Sears began a series of studies in bedsharing after he noticed his wife "mothering" in her sleep: "They would gravitate toward one another, and Martha, by some internal sensor, would turn toward baby and nurse or touch her, and the pair would peacefully drift back to sleep, often without either member awakening."

This easy, on-demand nighttime attention means babies need not fully awaken during the night - whereas a solitary sleeper might have to cry loudly, a bedsharing baby is reassured by her mother's presence without even being conscious. Not surprisingly, bedsharing babies grow up to report fewer fears and sleep problems than their solitary-sleeping peers.

The benefits even continue later in life. Numerous studies have linked bedsharing with better behavior, less fear, fewer psychiatric problems, less dependence, and higher self-esteem for children; while, as adults, former cosleepers exhibit "a greater satisfaction with life", stronger sexual identities, and higher levels of confidence.

Making bedsharing safe

As adult beds are not designed with infant safety in mind, some simple modifications are a good idea.

The mattress should be firm and fit snugly against the headboard. Overly fluffy or heavy bedding should be avoided, and all bedding should be neatly tucked in to minimise the risk of smothering. Covers should be kept away from the baby's face. Some parents wear long-sleeved tops and sleep with the bedclothes around their waists; others place the baby in a sleep sack on top of the covers. Furniture should be moved away from the bed to prevent large chinks in which an infant might become wedged.

If parents are bedsharing with two children at once, the older child should never sleep right next to the baby. Overlying is a rare occurrence for adults because their spatial awareness is maintained even during sleep. Children, however, tend to sleep deeply and lack this sense (hence why children occasionally fall out of bed), and are therefore much more likely to smother a baby. To avoid this risk, parents often arrange the family bed in a baby-mother-father-child pattern.

And the number one tip for happy cosleeping? Don't mention it to unsympathetic ears. Life's too short - you could be napping with your baby!

Cosleeping: Another option

For parents considered "high risk" for bedsharing, cosleeping can safely offer many bedsharing benefits. Often incorrectly used interchangeably with bedsharing, the term "cosleeping" refers to any situation where the baby is sleeping within arms' reach of the mother. Placing the baby on a separate sleeping surface, such as a hammock, bedside crib, or sidecar eliminates the risk of response-impaired adults overlying him. While cosleeping does not provide some of the benefits of bedsharing, such as effortless breastfeeding, it is still safer for the baby than sleeping in a separate room.

Sarah Tennant bedshares in Hamilton with her husband and five-month-old daughter Rowan, but not their two chickens.

AS FEATURED IN ISSUE 4 OF OHbaby! MAGAZINE. CHECK OUT OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE BELOW