Rethinking screentime: parent like a tech exec

Miriam Mcaleb offers research-based guidance on navigating our love-hate relationship with screentime.

Caution: if you get hit with a wave of guilt while reading this article, please try to replace it with a cushion of compassion for yourself. Remember, you’re feeling guilty about something which is much bigger than you (think of it as David vs Goliath, or you vs a tech giant). You’re also not alone: 85 percent of New Zealand parents say technology use and the impact of screentime is a top concern, according to the nib State of the Nation Parenting Survey (see below). This Māori proverb sums up the situation: He waka eke noa. We’re all in this waka together.

Seeing as the topic is front-of-mind for so many of us, let’s put our brave pants on and have the conversation. Digital is here to stay, so let’s take time to clarify our thoughts on the topic. Unlike other parenting topics, this is one area we can’t just look to our predecessors for guidance, because parenting in the digital age is uncharted territory. So buckle up!

|

HERE'S WHAT NEW ZEALAND PARENTS REPORTED IN THE NIB STATE OF THE NATION PARENTING SURVEY:

The top two concerns parents have for their children today are:

The top concerns highlighted by parents around their children’s device use included:

Conflict and device usage:

|

Past generations did not have the pressure of competing for their children’s attention to the extent that we do. When our great-grandparents were raising our grandparents they didn’t have to worry that the values they were trying to instil (such as lying is bad, being smart is more important than being pretty, or ‘do the mahi, get the treats’) were being contradicted by some mighty advertising budgets or by endorsement-accepting influencers. Sure, we have some benefits our great-grandparents did not (indoor plumbing is a beautiful thing!), but those of us parenting now also have worries that didn’t exist before. The threat of our children being commercially exploited is a daily occurrence, but it was unheard of for thousands of generations stretching peacefully into the past. Now our kids are marketed to before they can even talk. They recognise corporate logos before they can read. And as the number of screens in our homes increases, so does the number of opportunities for companies to wrap their tentacles around our kids.

Welcome to the attention economy, where we – and our children – are the product.

PARENT VS TECH GIANT

The stated goal of those who design tech and apps is ‘time on device’ – not your family’s wellbeing. Let’s face it, increasing ‘time on device’ is the opposite of what most parents are trying to achieve. If you’re finding it hard to get your child to switch off and re-engage with the whānau, that means a tech designer has done a good job with their ‘persuasive design’ strategies! Still, “It’s unreasonable to design services to be compulsive, and then reprimand children for being preoccupied with their devices,” says the report Disrupted Childhood, by the 5Rights Foundation. (You can find this excellent report at 5rightsfoundation.com/resources. It’s good stuff, so check it out – after the kids are in bed!)

This background information about the so-called ‘sticky’ design strategies used by tech companies is important because we need to understand the wider context for what can feel like lonely, in-home battles. Remember, this is bigger than just your family, and if you’re finding it a tense topic at your place, well, no wonder! Our natural desires for novelty, mastery and connection are being exploited and manipulated by those who answer to shareholders, not to ethics committees.

Some of those who have designed these addictive tools have come to see how problematic they can be and are speaking out against them. One famous example is former Google employee Tristan Harris who invented the ‘infinite scroll’ function on your phone. In June this year Harris testified to the US Senate about what he called the “asymmetric power of algorithms”, and poetically explained that “Because YouTube wants to maximise watch-time, it tilts the entire ant colony of humanity towards Crazytown.”

PARENT LIKE A TECH EXEC

The phrase ‘parent like a tech executive’ is actually shorthand for being low-tech or no-tech in your parenting, and in Silicon Valley, that practice extends into schools. Steve Jobs, who invented the iPad, didn’t let his kids use one. His explanation that iPads were not designed for children is also true of computers, smartphones, YouTube, and the internet itself: none of these things were designed for children.

So why are the children of Silicon Valley predominantly kept offline? Let’s look to our evolutionary history. How did we evolve this juicy brain and these dexterous fingers? How did we evolve a mind capable of imagining the iPad? We evolved the brains and bodies capable of creating such technology by having childhoods free of such technologies. We evolved these brains and bodies by being in relationships with adults who cared for us, gazed at us, sometimes growled at us, cuddled us and talked to us. We evolved these brains and bodies by having tonnes of time to play outside, use our bodies, dig in the dirt, watch clouds drift past, make up silly songs and bicker with our brothers. Children still need these things, but one of the problems with screentime is that it takes away time from those important activities. Numerous studies show that today’s children are spending too much time being utterly sedentary. Time spent sitting in front of a screen reduces the available time for climbing trees, playing Twister or skidding across the kitchen floor in your socks.

|

8 TECH LESSONS 1. Our children need us to protect them from the vultures of the attention economy. 2. Kids will be healthier if they sit less and play more. 3. Limit your own tech use, especially in the presence of your kids. One of my mantras is, “Save it till they sleep”. If you must engage with tech, say “Excuse me”. Yes, to babies too! 4. Be deliberate, intentional and purposeful. Avoid TV in the background – if you like the chatter, try the radio instead. 5. Take time to override device defaults that are designed to draw you in and keep you captive. For example, turn off notifications and autoplay so the settings serve you. 6. Remember, boredom is a blessing! It helps develop creative minds. 7. Why not try a tech sabbath where your family turns off all screens for a day, eg from 6am to 6pm on a Saturday. 8. Flick your phone onto flight mode for an hour or two each day for some uninterrupted quality time with the kids. |

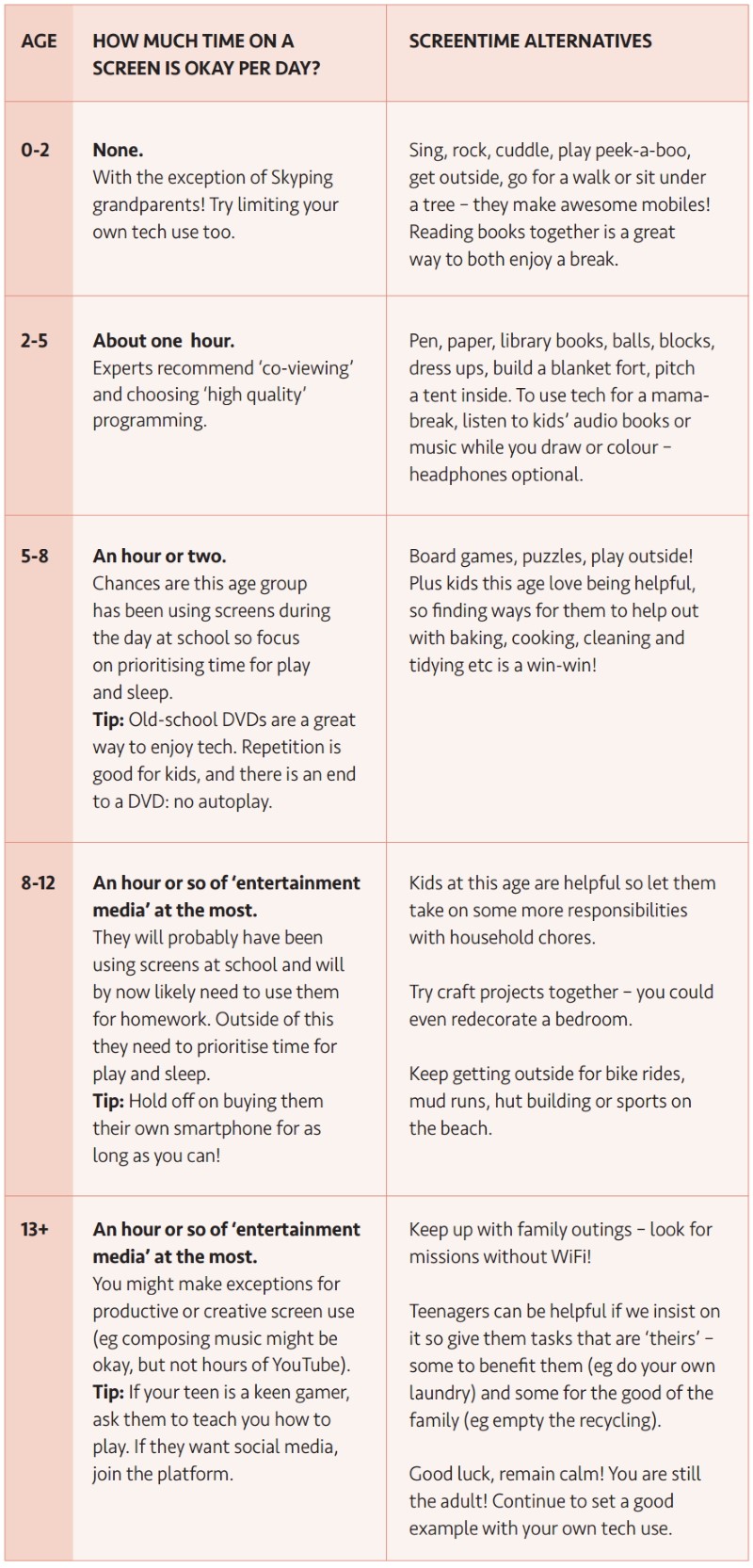

SCREEN ALTERNATIVES

As a mum, I understand the allure of switching on a screen for the kids. There are times you just can’t face cleaning up another play dough tea party or dealing with all the noise and bluster. But remind yourself that turning on a screen now is likely to lead to drama when you switch it off later, so only ever turn it on if you have first established the limits for turning it off. Set a timer, and stick to it. Know what is coming next and scaffold straight into that. Gird your loins for the complaints, but turn it off anyway!

I know this seems counterintuitive, but I’ve found that I have more success getting dinner cooked without grizzling if I can give myself to the kids (fully! And passionately!) for ten minutes before I start. If I can quiet my impatient inner-script for a few minutes and do some colouring near the food prep area, I can usually wriggle myself sideways into my chef’s role quite peacefully. Somehow, when my children ask to watch TV or to go on an iPad, they’ll accept my suggestion of “How about we draw together instead?” yet would reject me saying “No, sit here and draw.”

Also, there are plenty of alternatives between ‘full-on mess’ and ‘immobile screeniac’, such as books, puzzles, pencils, paper, marble tracks, blocks or (if your living arrangement allows) a bit of good old-fashioned “Go outside!”. The World Health Organisation summarises its findings like this: kids need to sit less and play more. That’s a worthy goal, which would certainly reduce the negative impacts associated with screentime. We know about the negative impacts of excessive screen use because there is plenty of peer-reviewed research highlighting the challenges it poses to child development and attention spans. But friends, the first lesson from the mountains of research papers I’ve read in the past few years is that we cannot have a conversation about our kids’ tech use until we have a conversation about our own.

LEAD BY EXAMPLE

There are dozens of studies that link the amount of parental screentime to the amount of screentime our kids have. Our own tech use is potentially problematic for other reasons too. When we’re distracted by our screens (and smartphone users pick up their phones on average 80 times a day) we’re not giving our full focus to our children. There’s mounting evidence of harm being done and the younger the child the more this is true. Parental phone use has been shown to negatively impact kids’ behaviour, language development, and socioemotional health. It might feel innocent enough – a quick check of a friend’s holiday pictures or a speedy reply to an email – but the accumulated effect of all that distraction is not benign. Even tiny babies are sensitive to interruptions in the flow of interaction, and these interruptions are associated with risks to infant mental health.

Okay, I’m calling a quick time out: if that information has induced a guilt-attack, please take a break. Do some deep breathing, hug your inner-self, and realise that you’ve probably never been told about these findings. Despite international health researchers calling for guidelines to let new parents know to limit their own screen use in the presence of their children, nobody includes such guidelines in their Well Child checks yet! (If you’re reading this Jacinda Ardern, give me a call!) Please drop the guilt though. You can’t do better if you don’t know better. And now you do.

Instead, let’s use the guilt to fire action at two levels. There’s the kind of action that comes with being an advocate around this issue: learn more, join a campaign, raise a little hell. The other type of action is the one in your own home, the one where you get serious about protecting your kids from the insatiable reach of the attention economy.

THE BENEFITS OF BOREDOM

Now, about those kids. What if I told you that one of the most loving things you could provide for your children was boredom? Michael Rich is a professor of paediatrics at Harvard Medical School, and he says “Boredom is the space in which creativity and imagination happen”. Back to the 5Rights report: “The capacity for boredom is the single most important development of childhood. The capacity to self-soothe, go into your mind, go into your imagination. Children who are constantly being stimulated by a phone don’t learn how to be alone, and if you don’t teach kids how to be alone, they’ll always be lonely.”

It’s clearly important to let our children have time to daydream and let their minds wander. In fact, it’s so important for their wellbeing that we brace ourselves for the cries of “I’m bored!” and are willing to tolerate some level of grizzling in the name of love! Be prepared to have these arguments day after day. My teen knows the rules about phone use, but I still have to offer daily reminders, a reality that neither of us enjoy. Just like I used to grit my teeth and keep reminding my kids to wash their hands after flushing, I’ll keep reminding them about our household screentime limits. For the sake of their healthy sleep patterns, their attention spans, their mental health, their physical wellbeing and for the sake of our relationship, I’ll make use of the best tech feature of all: the off switch.

Miriam McCaleb is a writer, researcher, teacher and mum who lives in the country at the edge of the internet. Despite the dodgy cell reception she still struggles to resist technological distraction. Visit her at baby.geek.nz – after the kids are in bed.

AS FEATURED IN ISSUE 47 OF OHbaby! MAGAZINE. CHECK OUT OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE BELOW

The potential impact of social media (89 percent)

The potential impact of social media (89 percent)