New generation help keep te reo Maori alive

The use of te reo Māori is on the rise. More parents are speaking te reo to their infants, in comparison to their own childhood. The number of toddlers of Māori descent who understand te reo has also increased. This information is revealed in a new policy brief from the Growing Up in New Zealand study that follows the lives of almost 7000 children from before birth into adulthood.

Twelve percent of all the children in the study were described by their mothers as understanding at least some te reo when they were two years old. Meanwhile, 40 percent of Māori two-year-olds understood at least some of the language. In comparison, around 20 percent of Māori parents reported understanding te reo Māori well or very well.

“It has been proposed that Māori language could be described as safe if 50 percent of Māori spoke Māori,” says Dr Te Kani Kingi, Māori Expert Advisor for the Growing Up in New Zealand study.

Te reo Māori remained a predominant, living language in the early post-colonial period, but by the mid-twentieth century concerns were raised that the language was dying out.

Initiatives since the 1980s, including kohanga reo and kura kaupapa, have focused on the revival of te reo Māori and have emphasised the importance of the language to New Zealand’s national identity, says Dr Kingi.

As described in the policy brief, it is rare for the parents of the new generation of New Zealand children to themselves have been raised in a Māori language environment. The study shows an encouraging change in that trend: by the time their own children were nine months old, 15 percent of mothers and 7 percent of fathers were speaking some te reo Māori to their infants.

Despite more children understanding te reo today, regular use of the language at home remains low. Less than 1 percent of children had a parent who was speaking mostly te reo Māori to their infants. The main motivations for those parents who used te reo as the primary language at home was to maintain their Māori culture, to bring up their child in a bilingual environment, and to ensure the child’s success later in life.

“The challenge for us is now to support those children who are hearing Māori as infants and understanding Maori at age two, and to turn them into active te reo speakers later in life,” says Dr Kingi.

- At the time of pregnancy, 5 percent of mothers and 3 percent of fathers described an ability to hold a conversation in te reo Māori

- In infancy, 15 percent of mothers and 7 percent of fathers spoke some te reo Māori to their children. Less than 1 percent of infants at nine months of age had a parent who was speaking to them mostly in te reo Māori

- 12 percent of all children are described as understanding at least some te reo Māori when they were two years old

- 40 percent of Māori children are described as understanding at least some te reo Māori when they were two years old

- Approximately 20 percent of Māori parents describe they are able to understand spoken te reo Māori, or able to speak te reo Māori, well or very well.

- A greater proportion of children are described as understanding te reo Māori at age two than the proportion of their parents that used te reo Māori in their own childhood, or that spoke conversational te reo Māori as adults.

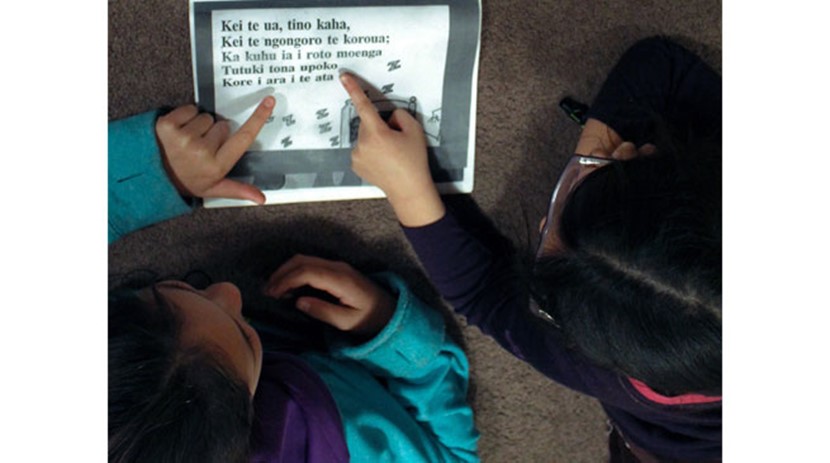

Image/ Growing Up In NZ