Broken but beautiful: one family's story

Expectant parents often declare their hope is simply for a healthy baby. For some families, however, children arrive with a prognosis for a life far from ordinary. One mother describes her exceptional family.

I’m a mother of two, a wife, and a health professional. I write this anonymously, partly to protect my children’s identity and partly to avoid having people pity me. Pity tends to arrive fairly soon after people hear about my children’s needs. I don’t need pity, but thanks anyway.

I write this with the hope of providing a voice from the other side – the side where things haven’t gone according to plan. The 'healthy' baby (“I don’t mind if it’s a boy or a girl, as long as it’s healthy”) hasn’t happened. Both of our children have pretty profound issues that have been life-threatening. One child has a significant developmental delay – he’s eight now, still in nappies, attends a special school, has seizures, and needs constant supervision to keep him safe. Our other child is six, has had open heart surgery (and will need more surgery) and is missing a kidney. My GP says we’ve been really unlucky, but I’m not so sure.

Often we grieve the arrival of a different child to what we expected. This applies if you got a girl and wanted a boy – it takes a period of adjustment, and letting go of the idea of the child you had in mind. In my experience, it’s the same process when a child with a disability arrives – adjustment, and a sense of grief for the child (and life) you thought you’d have. The added issue with a disabled child though is that family and friends seem to go through a grief process too, and some seem to never really adjust. I think this happens for many reasons, including society’s attitudes towards difference and disability. There’s the unspoken (well, sometimes it is spoken!) message that a child with a disability is less of a person. They’re worth less. They’re a burden rather than a blessing.

We’ve had a wide range of responses to our situation, from “God chose you to be their parents – you must be really strong people”, to “No offence, but I’d rather not have a child, than have a child like yours”. (True story, that really happened. The bit that made me cackle was the “No offence”). Aside from one tear-laden car-based meltdown, right after we’d been told one of our children might not survive the day, when we cried “Why us?!”, we’ve mostly taken it on the chin. Don’t get me wrong, it’s not easy. Some days it’s hard – really hard. But, just like the cliché, I genuinely wouldn’t have it any other way.

Counting blessings

The journey so far hasn’t been nearly as bad as I thought it would be. In fact, it’s been pretty darn good. Society had conditioned me to expect that I’d have a bad life with a disabled child. But so many things have surprised me, and taught me that this attitude is so very wrong. For example, the strength of love I feel for my disabled child is exactly the same as I feel for my typically developing child. Yes, he dribbles, picks old chewing gum off the footpath to eat, has big tantrums and is getting heavier to carry, yet I’m often blind-sided by the strength of my love for him and how far I’d go to protect him. I love different things about each of my children, but I love them both with a fierce passion. And I’ve never really wanted our disabled child to be any different. Because if you took away the hard bits, he’d be a different child, and I love the one we’ve got.

Despite his difficulties, he’s the friendliest child I know. Hugs for strangers, “I love you” for everyone who gives him eye contact, and “I’m SO pleased to see you” for special people. He regularly makes us laugh. When leaving school recently he announced “I love you, Andrew” to a group of his adoring teachers, adding “but I don’t love YOU, Sue”.

Other children his age are beginning to prefer alone time to family time, but not our boy. He beams from ear to ear when he glimpses me at school pick-up, and giggles uncontrollably at his favourite cartoons. When I’m not smiling, he asks “Why you sad? I will make you happy” and uses his fingers to push the corners of my mouth up.

In many ways, I see us as fairly fortunate. With our high needs child, I’ll never have to wonder if he’s being driven home by a drunk friend, or is unsafe out late in a bar. I’ll not have to worry about losing him to an exciting job opportunity overseas, or to a girlfriend who’ll break his heart. And, in a weird way, it’s comforting to know what we’ve got on our plate right from the beginning.

We’re also fortunate not to have many of the difficulties that some friends in the special needs community experience. Whenever I’m tempted to feel sorry for myself, my mind takes me to how much more difficult things could be. Some say “Comparison is the thief of joy”, but comparing oneself to those on a rougher road can bring sobering perspective.

Another way in which we’re fortunate is that our values have also been unpacked and repacked over the last nine years. I had always thought that my children would attend the ‘right’ schools in the ‘right’ areas, and go on to do the ‘right’ degree(s) at university. Currently, our boys are attending a low decile school with a special needs unit (which is a truly excellent place), and I genuinely couldn’t care less if neither child goes on to university. I’m far more interested in supporting them to strive for contentment, joy, and meaningful relationships with other people. And I can honestly say that this would not be the case if life hadn’t thrown us this curve ball.

A different pace

Having children with extra needs has also made us slow down our lives – and that’s a very good thing. My personality leans towards frantic planning and constant activity, but that’s not possible with a child who is easily overwhelmed, and gets really tired often. Rather than a different activity after school each day, we can really only manage one thing each per week. We have lots of down-time after school, lying on bean bags listening to Beethoven’s fifth symphony. Who knew that having a special needs child would awaken my interest in classical music?

Our situation has also helped me soften the hard ambition I used to cling to. I work part time in a role that’s very different to what I’d be doing if my children had typical needs. For a while I fought against this, and felt frustrated that I wouldn’t be climbing the corporate ladder with the speed I thought I should, but now I see things in a very different light. I’ll climb, but when the time is right. I’ve had the privilege (yes, privilege) of being reminded repeatedly that life is so very short.

Of course there are times when it’s hard and it feels really unfair that our beloved boys have so much on their plate. Sometimes I’d like not to have to change an eight-year-old’s dirty nappy, or explain to a six-year-old why he’s got a ‘zip’ on his chest. But I feel strongly that the road to rage and despair is paved with self-pity and feelings of injustice and unfairness. Our situation is what it is. There are small things we can do to change some aspects, but really it’s here to stay. I consciously try to turn my attention to that which we’re blessed with – like a good free health system. A good school. And months at a time with-out hospital appointments (this is new for us).

Testing times

There are increasingly sophisticated tests available these days, which provide huge amounts of information for parents-to-be about things that may be ‘wrong’ with their unborn child. This information can be useful but often results in fear-filled irreversible decisions. And the information you’re given is not the complete picture. As Professor Stephen Robertson, a clinical geneticist, says in Rachel Callander’s beautiful book The Super Power Baby Project, “No genetic test can predict anyone’s personality, talents and temperament”.

I’ll leave the science to the geneticists and the ethics to another conversation, but I hope my words will provide a little more balance to the bleak picture that’s presented when you surf the internet with the names of the disorder/s that your unborn child may have. From one mum to another, here’s my advice if you’re facing a journey that’s not what you expected:

■ Like you, I too wondered if I could manage a child with special needs. And I can. And you will too.

■ The thought of it is much, much worse than the reality. It’s natural to fear the unfamiliar, but being afraid doesn’t mean you can’t or shouldn’t.

■ There may be wobbles, but you will love your child with a fierce passion, whether they’re disabled or not. And that love will get you through almost anything.

■ You will wish that things weren’t so hard sometimes, but you will not wish for a different child.

The Japanese have an art called Kintsugi, whereby they repair broken pottery with precious metals, like gold or platinum. Rather than trying to disguise the cracks, they accentuate them. They apparently believe that when something has suffered damage, it becomes part of the history of that thing. I feel that about myself, and our little family. As individual parents, and as a family unit, we’ve taken our share of hits and have felt shattered at times. But our relationships are now stronger and more precious. Our values and priorities have been refined and repaired. We’re more beautiful for having been broken.

AS FEATURED IN ISSUE 37 OF OHbaby! MAGAZINE. CHECK OUT OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE BELOW

Optimise your chance of conception

- How do you optimise your chances of...

Obstetrician or midwife: how & why to choose

- Why do some people choose a midwife and...

The importance of iron in pregnancy

- When it comes to iron in pregnancy, it’s very...

Labour of love: what is labour REALLY like?

- You’re in labour!' It's a loaded statement,...

24 hours in a birth centre

- Sarah Tennant spent 24 hours in a birthing...

The power and purpose of sleep

- At the end of the day, baby whisperer Dorothy...

Tongue-tie: cause and effect

- Tongue-tie seems like the condition every new...

From 'goo' to 'go: baby's language development

- From "goo" to "go", language development can...

Paws for thought: does your little one need a pet?

- Sarah Tennant weighs in on the ‘shall we get...

Fashion forward: clothes for the cool kids

- Stay cool, calm and collected in black...

Broken but beautiful: one family's story

- Expectant parents often declare their hope is...

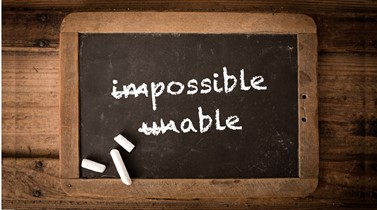

How to encourage a growth mindset

- Gretchen Carroll explores how parents can...

Books to warm little hearts

- Warm the hearts and tickle the minds of your...