How to be the type of boss your kids really need

Clinical psychologist Melanie Woodfield talks parenting styles and explains how taking charge is not a bad thing.

What do you do if your child won’t have a bath?” demanded the ad on my social media feed recently, “For everyone saying ‘force them’, I hear you saying that power is more important than the relationship with your child”. The ad went on to suggest that 'the science' tells us that expulsions from school, behaviour problems, and even youth suicide result from forceful parenting, which is 'a way of the past'.

As a child psychologist who has been working with children with challenging behaviour for 20 years, I have many thoughts about this. I may have even sighed aloud. Unfortunately, this kind of emotive language works. It makes a parent reading it feel that they’re not parenting how they are supposed to. They’re somehow doing it wrong. Therefore, they need to sign up to the programme to prevent serious harm to their child. Unfortunately, as with many things in life, it’s not that simple. In fact, taking charge in a warm-yet-firm way may actually guard against some of the awful outcomes that the ad threatens, and foster children’s autonomy.

AS TODDLERS, THEY OFTEN START TO DEVELOP THIS SENSE OF INDEPENDENCE AND PERSONAL CONTROL CONTROL OVER THEIR TOILETING, FOR EXAMPLE. BUT IT MIGHT NOT BE UNTIL ADOLESCENCE THAT THEY DEVELOP AUTONOMY AROUND THEIR FINANCES.

Power hungry?

Autonomy is an interesting word. From the Greek words for self, and law, it usually means self-governing, or freedom from external controls. But none of us are completely free of external controls. We’re autonomous within limits that change as we mature from infancy to adulthood. That’s why it’s really important to consider autonomy in light of the child’s developmental stage. For instance, in the earlier example of the bath, I wonder how old is this hypothetical child? Do they have any developmental delays or physical limitations? The extent to which a parent should take charge (let’s use that phrase, instead of ‘force them’) and pop them in the bath depends on lots of things, including whether the child is 18 months or 18 years. Children develop autonomy in different areas of their life at different stages. As toddlers, they often start to develop this sense of independence and personal control over their toileting, for example. But it might not be until adolescence that they develop autonomy around their finances. And all the way through childhood, they benefit from scaffolding from parents. Being supported to do that which they can independently, and having parents take charge of that which they can’t, provides the ideal setting for autonomy to develop.

There are a couple of areas where this can be a bit more complex. Body autonomy and consent is one of them. Parents quite rightly often want to teach children from an early age that if they are not comfortable with touch, it needs to stop. A recent book for young children written by Charlotte Barkla sums this up in the title: “From my head to my toes, I say what goes”. “I might say yes to pillow fights; a kiss when I'm tucked in at night. I might say no to climbing high, a tickling game or a hug goodbye”. These conversations are incredibly important. And I’m always impressed when books make these ideas practical and relevant for children (younger children struggle developmentally with abstract concepts). But with preschoolers, this can rub up against the daily realities of parents needing to take charge sometimes. What if the child refuses to hug grandma, and it’s about being stroppy or shy, rather than observing their own limits around body autonomy? Stroppiness and shyness might invite a different response from the parent. What if a preschooler refuses to have their nails cut, or refuses to allow the doctor to review their rash? Is the parent wrong or bad for insisting? Does this dismantle all the good work the parent has done around supporting the child’s body autonomy? These are heavy and complex questions. And – as is often the case – there aren’t necessarily clear-cut answers. Control is not *always* bad, and autonomy is not *always* good.

Parents as CEOs

In terms of control, hierarchies in family structures are important. Salvador Minuchin, a researcher from the 1970s whose work has been incredibly influential, suggested that there are subsystems within a family (the sibling subsystem, the parent subsystem) that are organised in a hierarchical way, with parents having the leadership role in the executive subsystem.

I applied this understanding to choosing an intermediate school for my youngest child a wee while ago. I explained to him that as parents, we are the CEOs of an imaginary company (ie our family). We make the ultimate decisions about big things like choosing a school. That’s our responsibility, and we wear the consequences if we make a decision that has outcomes we didn’t expect. But he is an incredibly important ‘shareholder’. We want to hear his opinions, perspectives and preferences. And we will absolutely take those into account. We will also take into account things that haven’t necessarily occurred to him and that he doesn’t need to think about at his age (school fees, transport logistics etc). The beauty of this collaborative approach is that if things don’t work out well at his new school, he’s not burdened or weighed down with the responsibility of having made the “wrong” decision (though as a side note, I’d argue that every child is different, and every school has pros and cons, and there’s usually not one ‘perfect’ school).

Parenting styles

Now, parenting styles absolutely must be thought about within the context of the family’s ethnicity, cultural norms, family structures and ideas. But generally, research has pretty consistently shown that the ideal style for good child outcomes is authoritative (high warmth, high firmness). Interestingly, some researchers have suggested that it’s not just the control that makes the difference, but the responsive, two-way communication between parent and child that really supports a child’s developing autonomy. Here is Diana Baumrind’s description from the 1960s of a classic authoritative mum, that is still relevant to us today:

She encourages verbal give and take, and shares with the child the reasoning behind her policy… She recognises her own special rights as an adult, but also the child's individual interests and special ways. She affirms the child's present qualities, but also sets standards for future conduct. She uses reason as well as power to achieve her objectives.

She does not base her decisions on group consensus or the individual child's desires; but also does not regard herself as infallible or divinely inspired.

What a fantastic roadmap. So we need to be flexible rather than rigid, and allow two-way, responsive communication with our child. That sounds like an approach that would preserve (and even enhance) the parent-child relationship. Coming back to the social media ad at the beginning – it’s not power OR the relationship, but taking charge within a secure relationship between the parent and the child.

Keeping calm and carrying on

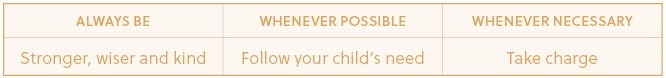

There are ways of taking charge that are affirming and respectful. I love the phrase that the Circle of Security programme uses – they suggest that parents need to be four things: bigger, stronger, wiser and kind. Bigger and stronger isn’t being cruel or mean. And wiser and kind isn’t being a pushover or weak. It’s about holding all four of these in balance. The table below sums it up nicely.

So what does this mean in practise?

+ Pick your moments. If your child is exhausted, and you’re at the supermarket, don’t give an instruction, expect it to be immediately obeyed, and enforce harsh consequences if it’s refused or ignored.

+ Give brief, age-appropriate explanations alongside instructions. “Put your shoes on right now!” feels a little different to “It’s almost time to go to kindy. Please bring your shoes to me”. And a wee tip: pop the explanation first, then the instruction. That leaves the instruction front and centre in your child’s mind, and they’re less likely to forget it.

+ If your child replies with a calm, sensible request or alternative suggestion, consider it, and explain why. “Since you asked so nicely, and we have a few minutes spare, yes you can.” Communicating that your ‘rule’ or expectation hasn’t changed, but you’re willing to be flexible on this occasion adds real warmth and helps kids feel heard. It also models social skills and respectful communication to them.

+ Think about what is reasonable for your child to be in charge of, versus what is probably beyond their developmental capacity, emotion regulation abilities, temperamental style or distress tolerance abilities. It’ll differ from child to child, and it’ll differ according to your family’s cultural expectations, your family values, and your own expectations (which are probably rooted in how you were raised).

+ It can be useful to talk directly with children about what they have control over, and what is an adult’s decision to make. Your child might be 'the boss of' what they wear to kindy (heck, if you can’t wear pink butterfly wings then, when can you?), or 'the boss of' which pillow they want on their bed. But the adults are 'the boss of' where we live, what’s for dinner, and whether we’re going to grandma’s place or not.

+ Try asking yourself a few questions in the moment. Things like ‘How can I truly “hear” her, while also getting her to do what she needs to do right now?’

Children need fair and reasonable limits, set by loving caregivers, so that they can develop their own autonomy and sense of self, within safe boundaries. Here is my suggestion: we can have both. We can have a deep and warm relationship with our child and also take charge when we need to.

Dr Melanie Woodfield is a mother of two young men, clinical psychologist and researcher from Auckland.

AS FEATURED IN ISSUE 61 OF OHbaby! MAGAZINE. CHECK OUT OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE BELOW