In those days: a wartime babyhood

Acclaimed NZ writer David Hill reflects on his own baby days and childhood in an era influenced by war, rationing and the authority of Plunket.

My mum always claimed that the first thing she heard as she came out of the anaesthetic was an old valve radio at the end of the ward, broadcasting the 9pm BBC News. It wasn’t good news. The Germans were advancing from Libya into Egypt, while Allied forces fought stubborn rear-guard battles. Those forces included New Zealanders. Those New Zealanders included my mother’s brothers Adam and John.

It was a few seconds till my mother understood she felt sore. She tried to move. Instantly, a figure in starched white head-dress and matching uniform appeared by the bed. “Just rest, Mrs Hill. Congratulations – you’ve got a healthy baby boy.” It was June 24, 1942, in McHardy Home on Napier Hill. I’d just appeared on the planet.

You’ll notice I mentioned anaesthetic. It was the way of things back then. Knock mother out so she wasn’t in pain or distress as baby arrived. The realisation that baby might also be partly knocked out, even potentially damaged in the process, didn’t come till later.

It may have been the best option in my mother’s case. She was 36 years old, and I was to be their only child. Conception or birth problems? I’ve no idea. My dear Mum and Dad were the generation when decent folk didn’t talk about such things.

Yes, they were decent. They were also caring, even doting. I couldn’t have hoped for better parents, though I didn’t really understand that till I had kids of my own. I was nurtured, protected, guided.

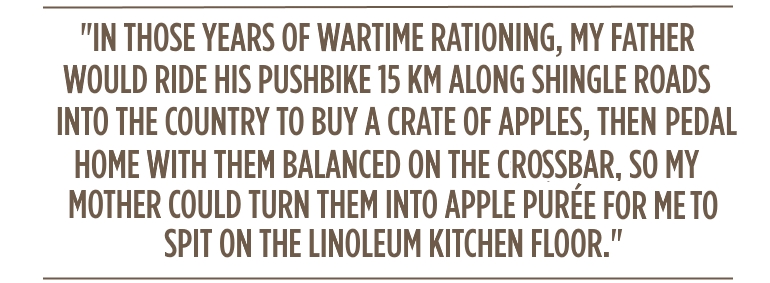

DEVOTION AND SACRIFICE

In those years of wartime rationing, my father would ride his pushbike 15 km along shingle roads into the country to buy a crate of apples, then pedal home with them balanced on the crossbar, so my mother could turn them into apple purée for me to spit on the linoleum kitchen floor. Later, he saved his chocolate rations from the Dad’s Army Home Guard for me. Like most of my generation, I grew up with a mouth full of fillings.

They had pet names for me. “Deedle” was the most embarrassing, a form of “Little David”, I suppose. They used it for years, till my friends started teasing me, then made themselves stop.

They were tactile, also – unusually so for the 1940s-50s. Dad would ruffle my hair, put an arm around me. Mum would kiss me goodnight, and again in the morning (after which she’d tell me to go wash my face). I always knew I was cherished.

I was also disciplined. That means my parents hit me. It still sounds jolting when I write it down. My mother would smack me on the legs with her hand. Once when she caught me throwing a stone at our old cat, she slapped my face so hard that my head buzzed for days. My father would demand “You want to feel the back of my hand?”. In fact, I seldom did feel it, and if he ever smacked me, he’d go off and dig in the garden for an hour.

“Spare the rod and spoil the child.” This was still the rule in my babyhood and childhood. I’ve heard people my age claim “It never did me any harm”. Well, it harmed me: I told lies to cover things up; for a while, I developed a stammer. Yet I always knew that my parents acted as they did because they loved me.

GOOD SOLID ADVICE

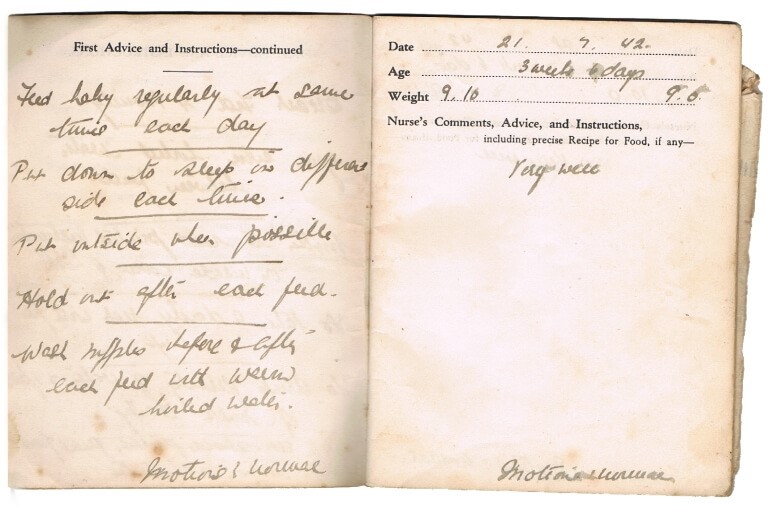

For my first months of life, I was a Plunket Baby. Seventy years (ouch!) ago, Plunket was a lifeline for young mothers, sometimes literally. Plunket Nurse/Mother relationships are flexible partnerships these days, but in the 1940s, Nurse always knew best. She gave advice (make that orders) and Mother did what she was told. Feeding, sleep, weaning, solids, toilet training: all proceeded according to a fixed timetable. And all were recorded in the Plunket Book.

I still have my Plunket Book, officially called The Well Baby Book. It’s the only visual record I have of my childhood. There aren’t any photos. We didn’t have a camera; not many did in those years.

The cover of my book vanished long ago. Maybe I ate it, with the seven teeth recorded in its last entry. Its first surviving pages are a record of my vital statistics at birth, plus an invitation from Gertrude Smith, Hon Sec of the Napier Plunket Branch, to donate five shillings and become a member.

Opposite, hand-written in black ink, is a list of instructions for Mum: “Drink plenty of water, and one pint of milk daily. Avoid sauce, pickles, and fried food. Rest with feet up while baby sleeps”. Yeah, right.

It records the Plunket Nurse’s weekly visits. My weight rose steadily from 7 pounds 11 ounces (about 3.3 kg) to 28 pounds 8 ounces (12.8 kg) at the end of 67 weeks. Most of the time I was “Very Well”. Thanks, Mum. And most of the time – cringe, cringe – I produced “Regular Motions”. Plunket in the 1940s was much concerned with motions.

My Plunket Book is full of firm instructions. “Feed baby regularly at same time each day. Put down to sleep on different side each time.” Nurse noted approvingly that I was weaned at 17 weeks. If I hadn’t been, I suspect my mother would have been told to pull herself together. Nurse also recommended a lot of Barley Water, and something disgusting called ‘Prune Pulp’.

She was keen on ultra-violet as well. “Put outside where possible.... Give sun bath.” Mum used to enthuse over how much time I’d spent in the sun: “You were as brown as a berry”. These days, I get checked for melanoma. Of course, she wasn’t to know.

FOR HEALTH AND STRENGTH

As I left babyhood, my parents filled me with cheese, egg yolks, full-cream milk, red meat, and all the other things that the 1940s-50s knew were best for you. I suspect they went without sometimes, so that I could have the nourishing stuff.

When I was almost two, and broke my leg, my father carried me in his arms over a kilometre to Napier Hospital. They didn’t own a car till I was 15, and anyway, he wasn’t going to let me be bumped around in a taxi. When I got chicken pox just before my third birthday, Mum walked halfway across Napier in the middle of the night to get calamine lotion from a friend, and ease my itching.

They smoked, both of them. Outside, as I lay in my pram. Inside, around my highchair. If passive smoking had been heard of then, they’d have stopped immediately. They’d have given up any pleasure for my sake.

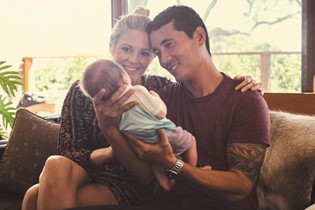

My mum died when I was 20. On my birthday that year, she’d hugged me and called me “Sonny”, which she hadn’t done since I was a toddler. It was almost as if she sensed what was coming. My dad died wonderfully, in his sleep 11 years later, after being able to dote on his baby grandson.

They’re buried together in a little rural cemetery outside Napier, beside the river where my mother swam as a girl. I live hundreds of kilometres away now, but every time I come back, I visit them, tell them what I’m doing, how much I owe them. I couldn’t have had a more cherished childhood. Thanks for everything, Mum and Dad.

David Hill is a writer, playwright, poet and columnist, best known for his popular and award-winning books and stories for young people. David lives in New Plymouth with his wife Beth. They have two grown-up children and two grandsons.

AS FEATURED IN ISSUE 45 OF OHbaby! MAGAZINE. CHECK OUT OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE BELOW