Conceiving medical miracles: the history of IVF

In vitro fertilisation (IVF) has been changing lives since 1969 and the process itself has changed too. What was once rare and complicated is now a mainstream practice, explains fertility specialist Dr Richard Fisher.

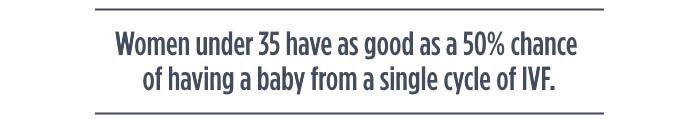

Initially, IVF was seen as a method of bypassing damaged fallopian tubes. Women who could not conceive because their fallopian tubes were blocked or severely damaged could use the technology to create embryos outside the body and to reimplant them inside the uterus without using the fallopian tubes. Today, IVF has much wider uses than this, and nearly all forms of sub-fertility can potentially be treated by using IVF and embryo transfer. In the early days, a 5% chance of having a baby was considered an exciting prospect for many couples, but, fortunately, these rates have improved significantly and now only those in their mid-40s remain with such a low success rate. Women under 35 have as good as a 50% chance of having a baby from a single cycle of IVF.

In the past few decades, the process of IVF has simplified greatly, both for those having the treatment and those involved in delivering it. New drugs are now available which can control when ovulation occurs, so it is no longer necessary to do egg retrievals very late at night. Also, current protocols for stimulating the ovaries allow us to obtain more eggs than we used to. It was not uncommon in the early 1980s to obtain only one or two eggs and, consequently, have no embryos to replace. The use of newer and different drugs has made the process of ovarian stimulation much more controllable and more successful.

The process of IVF and embryo transfer initially involves the stimulation of the ovaries to make more eggs than usual. In a normal menstrual cycle, only one egg is produced from a single mature follicle (a fluid-filled cystic structure which develops around the egg). Using injections of a follicle-stimulating hormone, the ovary can be stimulated to produce multiple follicles from which eggs can be obtained. To ensure that the eggs are mature and available for retrieval at a reasonable time, two other drugs are used. One, which controls the pituitary's ability to produce its own FSH and LH (luteinising hormone which triggers ovulation), and hCG, which is used to trigger ovulation in this artificial cycle. There are a myriad of different stimulation protocols available, none of which have proved significantly superior to any other, although in individuals a different protocol might be chosen because of that individual's previous history.

In the early 1980s, eggs were retrieved laproscopically, a procedure requiring general anaesthesia and what is now commonly known as keyhole surgery. With the advent of ultrasound and the development of transvaginal ultrasound probes, egg retrieval is now invariably done under sedation and ultrasound control by passing a needle through the top of the vagina into the developing follicles and aspirating the fluid from within them. Eggs can be obtained from around 60-70% of follicles. Most of these eggs will be mature, but some will be immature and not suitable for fertilisation.

Once eggs are available, they will be fertilised in one of two ways. In circumstances where sperm quality appears satisfactory, then the eggs and sperm are laid next to each other in small dishes in the laboratory and fertilisation occurs as it does in nature. Where sperm quality is doubtful, sperm injection occurs, with individual sperm being picked up and injected into the cytoplasm of the egg.

Around 70% of eggs become fertilised, although this does vary from couple to couple. Initially, fertilisation is seen as the presence of two nuclei inside a single cell and, over the next two days, these embryos will divide into two, four, and eight cells. Embryos that have divided into eight cells are most commonly replaced into the uterus.

Whereas multiple embryos were transferred in the past, with the improvement in implantation rates (that is, the chance of a single embryo implanting on replacement), there has been a move towards single embryo transfer in younger women. As a consequence of this, other embryos that are considered to have good potential for implantation themselves are available for freezing. The embryo, or embryos, being replaced are placed within the uterus, through the cervix, in a fine catheter under ultrasound control. Although embryo quality is likely to be the prime determinate of success, new techniques such as ultrasound-guided replacement have improved pregnancy rates further.

On occasion, embryos are replaced five days after fertilisation as blastocysts. If an embryo can get to the blastocyst stage in culture, this is further proof of its high chance of implantation. It doesn't make embryos previously seen at eight cells any better, but just helps us select which are the best. Consequently, when there are a large number of embryos available on Day Three with a seemingly good chance of success, embryos can be grown on to Day Five so we can be even more selective about which embryos to replace. In good laboratories, there is little risk in growing embryos these extra two days. embryos can also be frozen at this stage.

IVF, like all medical treatments, is not without risk and side effects. The drugs used can cause mood swings and commonly a feeling of tiredness. Even though egg collection is normally done under sedation, some pain can be felt at the time of egg collection, but most people find this quite acceptable.

After egg collection, there are risks of infection and bleeding, although both are very rare. The most significant risk is the development of a problem called ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, which occurs in about 2-3% of women having treatment. Untreated, severe OHSS can cause blood clots, stroke and even death. While these risks are small, it is important to recognise that they exist. Mostly ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome can be managed as an outpatient, although around 1% of women may be admitted to hospital.

Children born following IVF are being followed up in a number of centres around the world. The chance of congenital abnormalities in children is about a third higher than that for children conceived naturally. This means a chance of around four per 100 births instead of three per 100 births. There might be a slightly higher rate of chromosomal abnormality in children conceived using ICSI. The chance of abnormalities such as Down's Syndrome is the same in IVF and ICSI pregnancies as it is in the general population. No one is sure as to whether this increase in congenital abnormality is associated with the process of IVF, or with an underlying cause of infertility. There are a few very rare diseases that seem to occur more commonly following IVF and Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI). The incidence following IVF is still around one in 2000.

With the increase in pregnancy rate over the years, IVF has more commonly become a first-line treatment, rather than the last-ditch one it started as. For many couples, using IVF as their primary treatment is a much more sensible option than serial treatments with procedures that have a low chance of success. In the end, individual couples need to make their own decisions about what treatment is suitable for them or not. However, not conceiving following simple treatment feels every bit as bad as not conceiving after more complex ones.

In New Zealand, access to publicly funded IVF is limited. Couples who have a very poor chance of success by themselves are eligible for treatment earlier than those who appear to have a higher chance. Most people will be eligible in time, providing they meet criteria that are also based around age, weight and smoking status. Although initially these criteria can sometimes appear unfair, they are based on maximising positive outcomes. Women who smoke, or who have a BMI of more than 32, have a significantly smaller chance of success than those who don't smoke or those carrying less weight. Waiting lists vary in different parts of the country, but providing the eligibility criteria are met, treatment can usually be started within one year.

Private treatment is available in New Zealand, at clinics that also provide publicly funded treatment. Fertility Associates have clinics in Auckland, Hamilton and Wellington. More information is available on the Fertility Associates website, www.fertilityassociates.co.nz.

What are the chances?

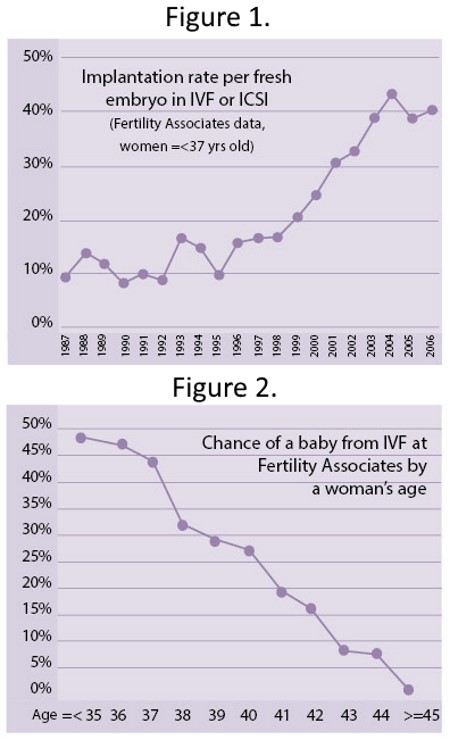

Success rates in IVF are dependent on maternal age. Figure 1 shows the chance of implantation of a single embryo according to maternal age. Whereas pregnancy rates have traditionally been quoted as chance of pregnancy in a fresh embryo transfer cycle, these days it is probably better to quote pregnancy rates that include subsequent transfers of frozen embryos within six months of initial egg retrieval. In older women, implantation rate does not reflect the pregnancy rate, as more than one embryo might be replaced. Figure 2 shows the chance of having a baby following IVF and subsequent frozen embryo replacements by age. As you can see, IVF is a very successful treatment in younger women, but becomes less so with advancing age.

Article published 2009.

|

Richard Fisher FRCOG, FRANZCOG, CREI together with Freddy Graham established Fertility Associates in 1987 after previously starting up New Zealand's integrated infertility medicine group at National Women's. He is New Zealand's foremost medical spokesperson on matters of reproductive health and has been an advocate for better access to care for couples with infertility throughout his career. He has four children and is married to Leigh, without whom he could never have practiced medicine with the enthusiasm and commitment that he has. |

AS FEATURED IN ISSUE 4 OF OHbaby! MAGAZINE. CHECK OUT OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE BELOW