Why are some babies breech?

Why is it some babies prefer to make their entrance to the world bottoms-up rather than head first? Here's the low-down on being breech.

Let's begin with a little history about the word breech, which, at least according to Google, has been used in some form for at least 800 years. It probably derived from the Latin word braca, which meant trousers. This morphed into breeches in old English, and so breech emerged as the word for the lower rear part of the body, or the buttocks.

Hence a breech presentation is when the buttocks are leading the baby’s way towards the pelvis, rather than being found up under the woman’s ribs with the head leading the way to the pelvis.

What are the chances?

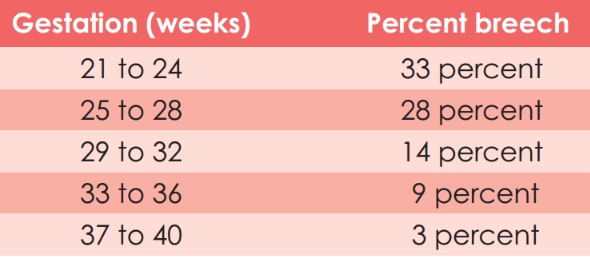

The likelihood of having a baby presenting as breech changes as pregnancy progresses, as shown in the table below:

Breech position is only of importance to midwives and obstetricians at about 37 weeks of pregnancy, because after that it is unlikely (although certainly not impossible) that the baby will turn round on its own. As most labours don’t start until after 37 weeks gestation, no specific action is required before then.

Turn, baby, turn

Breech presentation is often just another variation on normal and there's no one single reason why it happens.

Prematurity is commonly associated with breech presentation. Other predisposing factors include high parity, where relaxation of the uterine and abdominal wall muscles may remove the factors that make babies turn head-first. Sometimes the uterus may have an unusual shape which makes it impossible for the baby to turn; think of someone doing a forward roll and you will see that space is needed for that to occur. This can also be the case if there is less water around the baby than usual.

Conversely, excess water is also associated with breech presentation, probably because it provides too much room for continued turning. Occasionally, something may be preventing the head from settling into the pelvis, such as an ovarian cyst.

Breech presentation has also been associated with foetal abnormalities, which may affect the shape and size of the baby, or alter the way the baby moves around.

If you are diagnosed with a breech presentation at the end of the pregnancy, you will usually be offered a scan to confirm the situation and to see if there is an underlying cause. However, in the vast majority of cases, no abnormality is found.

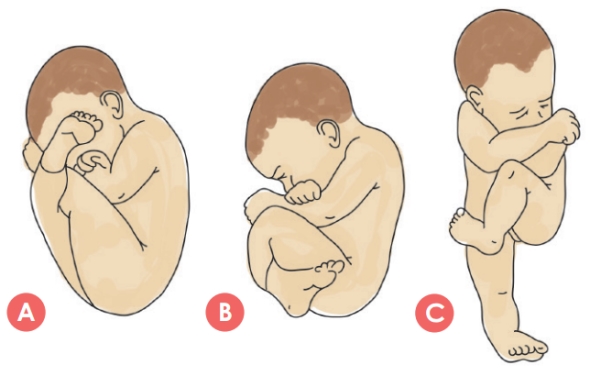

There are a number of different types of breech presentations, and they are usually classified as follows. The diagrams show the different types in labour.

a. Frank breech (also called extended): this is where the baby’s hips are flexed and legs extended over the anterior surface of the body. This accounts for about 45 to 50 percent of breech presentations.

b. Complete breech (also called full): this is where both the hips and legs are flexed. The baby appears to be sitting or squatting like a tailor, accounting for about 10 to 15 percent of breech presentations.

c. Footling breech: this is where one or both hips and knees are extended with one or both feet presenting, and accounts for about 35 to 45 percent of breech presentations.

The diagnosis of breech is usually made by the routine abdominal palpation that occurs during your pregnancy, when the baby’s growth is also being assessed. If your midwife or doctor is not sure whether or not your baby is breech after 36 or 37 weeks, then an ultrasound scan can be performed to remove the doubt. If the doubt first appears in labour, then a vaginal examination may help determine the baby’s presentation and, if breech, which type.

Why it matters

During the pregnancy, a breech presentation doesn’t matter until consideration is given to trying to move the baby to a head-first position, or until labour starts. It is the labour and birth that are associated with problems. The particular risk with labour is of umbilical cord prolapse, where the cord may become compressed or occluded between the presenting part of the baby and the mother’s pelvis. The incidence of cord prolapse is greatly increased in footling breeches (15-18%) and in complete breeches (4-6%), compared to frank breeches (0.5%) and head presentations (0.4%). In the worst case, this can lead to shortage of oxygen for the baby’s brain, which could cause permanent damage or death.

The risk posed during birth is a delay in the delivery of the head after the rest of the baby’s body has been born. At this point, the umbilical cord is again likely to be compressed between the baby and the mother, and therefore unable to deliver the oxygen the baby requires. A short delay probably doesn’t matter, providing the baby still has some reserves, but will obviously be more relevant in a baby who has already used up his reserves.

What to do

Efforts to get the baby to turn from breech to head-first have been widely studied. However, definitive evidence of benefit from any of them is lacking. Various turning techniques are often said to be successful, but they relate to individual women in whom the baby was probably going to turn anyway.

Suggested theories include positional changes (such as being on the floor on all fours, or sitting on a birth ball), acupuncture, homeopathy, and chiropractics. Moxibustion (burning a small cigar-shaped stick made of the dried herb, mugwort, near the small toe) was thought to be effective in a small trial, but later, larger trials have not proved this. I would not consider any of these until 36 or 37 weeks of pregnancy because most breech babies are going to turn on their own before then. If you do want to try one of these ideas, I suggest asking the practitioner you see just what their success rates are after 37 weeks.

One approach shown to be effective is to attempt external cephalic version (ECV) at, or after, 37 weeks. This is where your obstetrician tries to turn the baby around by putting pressure on your abdomen. ECV is successful for about 50% of women with breech presentations, and the success rate can be improved by giving the woman a drug to relax the uterine muscles (the drug does not harm the baby) and by the woman doing her best to relax the muscles of her abdomen. The procedure can be uncomfortable and should be abandoned if too painful. If a first attempt is unsuccessful, ECV can be repeated some days later.

If the ECV is successful, your baby is unlikely to turn back to breech, but this will be monitored by your LMC. ECV is safe, however, the baby’s heartbeat will be checked both before and after the procedure. Occasionally (about one in 200 cases) your baby might need to be delivered by emergency caesarean section after an ECV, because of changes in the baby’s heart rate or bleeding behind the placenta.

Special delivery

If you decide not to try ECV, or ECV is unsuccessful, then the decision about the most appropriate way to have your baby needs to be made. There are two options: a caesarean section or a vaginal breech birth, and the debate around the pros and cons of each continues. The evidence is clear that a planned C-section is safer for baby, but it is also true that vaginal breech birth can be successful and safe. Each woman and her baby should be assessed on their individual merits.

Guidelines around the world do make some general recommendations, which are:

• the obstetrician should be trained and experienced in delivering a breech baby vaginally.

• the place of birth should have facilities for emergency C-section.

• there are no particular features about the pregnancy that increase the risk to the baby from a vaginal breech birth.

Caesarean section does carry its own slightly increased risks (over vaginal birth) for the mother but does not carry any long-term health risks. It may pose some risks in future pregnancies, however, and these should be discussed with your LMC to enable the most informed decision about what to do.

This article was written for OHbaby! Magazine by a FRANZCOG (Fellowship of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists) Consultant Obstetrician currently practising in New Zealand.