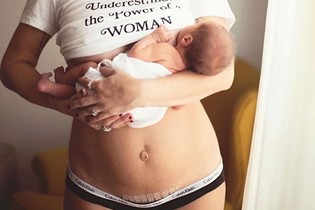

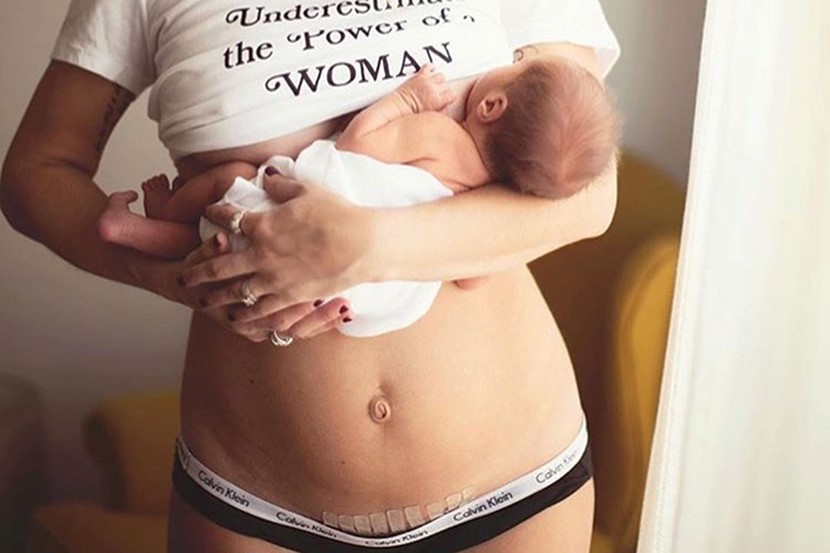

The lowdown on Caesarean Sections

OHbaby! expert obstetrician Dr Martin Sowter looks at why nearly a quarter of New Zealand mothers give birth by Caesarean section and at what risk.

Nearly one in four New Zealand babies will be born by Caesarean section this year. Despite, or perhaps because, a C-section is such a common surgical procedure, it continues to arouse regular media debate. For me as an obstetrician, the most frequent questions my patients ask are why they might need a C-section, what will happen and occasionally, why can't they just have one anyway.

Answering that first question of "why?" is the easiest. The second question about "what will happen?" is usually easy but does sometimes need a fully functioning crystal ball. Answering the third question of "why not?" or addressing the fears that led to it being asked is usually much more challenging.

Elective versus emergency C-sections

About half of all C-sections are "elective". This means they are planned in advance and hopefully take place at a pre-arranged time and date. The most common reason for having a planned or elective C-section in most developed countries is actually "previous C-section" - meaning the woman has delivered by C-section before for a whole range of possible reasons. But an elective section doesn't mean C-section without a medical reason.

All other Caesarean sections are "emergency" ones, though the degree of urgency will vary from "this baby should be delivered today" to "this baby should be delivered within the next 15 to 20 minutes".

Other reasons why an elective C-section might be considered include your baby being in a breech position (feet or bottom closest to the birth canal), having a multiple pregnancy or your baby appearing to be exceptionally large. In most of these cases your baby might not need to be born by C-section, but on balance the risks associated with delivering vaginally will make it a safer option.

There are a few unusual situations where the baby must always be born by C-section and these include having a placenta praevia, where the placenta lies below the baby in the womb preventing a vaginal delivery, or large fibroids in the pelvis which might stop the baby from entering the pelvis.

Most, but not all, emergency sections happen in labour. In some situations, such as where a baby has grown very poorly in the womb or a woman has developed pre-eclampsia, an emergency C-section might be arranged before labour begins naturally.

For women in labour, "failure to progress" and "foetal distress" will be the two commonest reasons for a C-section. Failure to progress essentially means that at some point your cervix has stopped dilating and the baby's head has stopped progressing down through your pelvis. This might be simply because your baby is too large, although this is actually a less common cause than the baby lying in an occipito-posterior position (an "OP baby"). With the baby in an OP position, the head doesn't fit well in the pelvis and labour can be prolonged as the baby's head does not descend far enough down through the pelvis.

"Foetal distress" sounds like a pretty terrible situation, but this term is often used if there is any possible concern about the baby's wellbeing during labour. A diagnosis of "foetal distress" is usually made by looking at the baby's heart rate pattern on a monitor. Most of the time these changes in heart rate pattern show very clearly that your baby is not coping with the stresses of labour. Occasionally it is less clear that there is a problem and an obstetrician may be called in to weigh up the possible risks of continuing with labour.

The lowdown of C-sections

Almost always if you are having a planned C-section it will be done with you awake, using an epidural or spinal anaesthetic (sometimes called a regional anaesthetic). With an elective operation there is time to ensure that the area of numbness or "block" is working well. Anaesthetists prefer to use a regional rather than general anaesthetic because it is safer. Of course for any woman, being awake and able to see and hold her baby as soon as he or she is born is preferable to delivering under a general anaesthetic.

Almost always if you are having a planned C-section it will be done with you awake, using an epidural or spinal anaesthetic (sometimes called a regional anaesthetic). With an elective operation there is time to ensure that the area of numbness or "block" is working well. Anaesthetists prefer to use a regional rather than general anaesthetic because it is safer. Of course for any woman, being awake and able to see and hold her baby as soon as he or she is born is preferable to delivering under a general anaesthetic.

There are a few occasions when a general anaesthetic will be recommended. The most common of these is when significant bleeding might be a risk. A general anaesthetic is more commonly used in emergency situations, although in most units at least 95% of emergency C-sections will be done using an epidural anaesthetic.

One surprise for the mother is just how many people are in the operating theatre. The obstetrician, anaesthetist and paediatrician may all have a doctor in training with them or a medical student observing (don't worry, it's been at least 20 years since multiple medical students have been in the theatre at the same time!). There will be a scrub nurse and at least one nurse "runner", and often at least one student nurse or new member of staff. An anaesthetic technician will be at "the top end" and your midwife will also usually be with you in theatre. All these people can add up to 10 or more, though many of them will be in theatre for only part of your operation. You can certainly object to having a student doctor in theatre, and in a properly run unit she should be introduced to you before you go into theatre. Relatively few couples seem to have a problem with medical or nursing students in theatre.

One issue that can arise with so many staff in theatre is they may not pick up on how frightened a couple might be or keep chatting to each other when the mum would prefer less noise and a calmer atmosphere. Do let your anaesthetist and obstetrician know if you feel frightened or overwhelmed - few people would describe having a C-section as a pleasant experience, but a good theatre team can help keep you calm and relaxed.

While it may seem like a cast of strangers is in the delivery room, in most cases you'll still get to choose only one person to be in theatre with you. This is partly because the anaesthetist needs to be able to monitor you without multiple support people distracting him. If you are having a general anaesthetic then you won't be able to have anybody else with you in the operating theatre while you are asleep, but most hospitals will allow your partner to come through with you into theatre until you have your anaesthetic.

Time to meet baby

Women often wonder if they can enjoy skin-to-skin time with their baby in the operating theatre. The answer is almost always an emphatic yes, and I do feel that as doctors and midwives we're sometimes overly keen to get the baby checked, weighed, wrapped and put in a plastic cot. Operating theatres can be a bit cold for a newborn, so generally he will be dried off and checked over briefly, then brought round and placed on your chest. The anaesthetist does need one of your arms for monitoring your pulse and blood pressure, and occasionally women feel nauseous after the baby is born. As long as you feel well you should be able to enjoy a cuddle with baby being weighed and dressed later. Sometimes the concerns about yourself or the baby that led to you delivering by C-section mean you need more intensive monitoring or the baby needs oxygen, which will cause a delay before you get to hold him. Breastfeeding in theatre before your surgery is finished can be more difficult, but if you let your midwife know she can usually help get your baby onto the breast.

Other questions about C-sections

Should you bring music, cameras and videos? We do get a few strange requests - I can remember one husband who requested that a special piece of music he had composed for the birth be played in theatre (think dolphins at play meets Enya). But generally most New Zealanders born by C-section emerge to the ever-present hum of Classic Gold - and long may Roy Orbison croon for us, I say. Cameras are welcome in most theatres but do make sure your slightly trembly partner knows how to use it. Policies on using videos in New Zealand theatres vary, but in most video recording is discouraged out of respect for staff privacy.

Can you or your husband watch the baby being born? There is usually a low screen to keep the operating field sterile, but this can be lowered and there is no reason why your partner can't watch the delivery. It's a good idea to let your obstetrician know this in advance so she can tell you what's happening. Relatively few men seem to want to see the baby being delivered, possibly worried they will faint on seeing their wife's "insides". However, I've yet to come across a new dad who wasn't amazed by seeing his child's delivery, even by C-section. For women there's no reason why the sterile screen can't be sufficiently lowered so you can see your baby as soon as he's born.

What happens next? Once the surgery is finished the three of you will go through to a recovery area and then up to the postnatal ward. The length of time women stay in hospital after a C-section varies widely, depending on how well feeding is going and how ft the woman is. Most women should be taking only tablets for pain relief after 24 hours, and would typically stay three or four nights in hospital after a C-section, or perhaps a day or two longer if breastfeeding is not going well.

When can you drive? My answer is what are you driving and where do you want to go? A slim, fit woman who has made an uneventful recovery should be fine to drive short distances as early as two weeks after a C-section; for less ft women recovery may be slower so it may not be safe to drive until after four weeks or more. In reality, putting a young baby into a car for a journey of any length on your own is usually associated with instant stress however your baby was delivered, and you are likely to prefer to be chauffeured for a few weeks at least.

Advising about exercise is sometimes a challenge, as people's perception of what constitutes exercise is so variable. Generally by four weeks any predictable exercise is likely to be fine, but team sports, digging up the garden or triathlon training (not as unlikely postnatal activities as you might think!) needs to wait until week six. Sex is usually fine somewhere between weeks four and six.

A general rule with any surgical procedure is that you should be feeling a bit better every day, and if not then something might be wrong. Wound infections are common and affect up to 10% of women who have had a C-section. In some cases simple wound care and antiseptic creams are needed but most require antibiotics.

Too posh to push… really?

Finally, how to answer that tricky third question of: "Why shouldn't I have a C-section?" Contrary to the impression sometimes portrayed in the media, relatively few women in New Zealand ask to deliver by C-section for no medical reason. What statistics are available suggest that about 1-2% of first-time mothers choose to deliver this way. We know that they are much more likely to be over 35, to have conceived through IVF or have had a prolonged period of infertility, and are more likely to have a history of other gynaecological problems before conceiving. They are also likely to have high levels of fear around childbirth and some studies suggest they are more likely to be pessimistic about their health. Occasionally, women who have had a traumatising birth will request delivery by C-section. Some women who might have a higher than usual chance of needing a C-section in labour might request one.

Undoubtedly there are a few women who book in for a Caesarean delivery as a "lifestyle option", but the vast majority of women requesting one without any firm medical reason have concerns about delivering vaginally that are very real and serious to them. Many of these women will become more confident about delivering vaginally as their pregnancy progresses, but for a few a planned Caesarean delivery will remain the most appropriate way for them to deliver. As long as the issues around the request have been explored (something which as doctors we could possibly do better) it would be unusual for a woman wishing to deliver this way to have her request declined.

Delivery by C-section does have a greater risk of post-delivery infection, bleeding and serious blood clots in the leg or lung, and your recovery is likely to take longer. In most New Zealand hospitals about 10-15% of first-time mothers will deliver by C-section in labour, meaning "planned vaginal delivery" will be a safer option for most women.

Martin Sowter (BSc MB ChB MD FRCOG FRANZCOG) is a part-time specialist at Auckland City Hospital in the fertility and menstrual disorders clinics. He also works privately as part of the specialist team at The Auckland Obstetric Centre. Over the last six years he has also been a regular visitor to the Cooks Islands under the auspices of NZAID helping the local specialists with gynaecological surgery. Martin is married to Alison, an eye surgeon, and has two daughters.

AS FEATURED IN ISSUE 17 OF OHbaby! MAGAZINE. CHECK OUT OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE BELOW