Episiotomies: the pros and cons

Is an episiotomy preferable to tearing 'down there' during labour? Midwife Paula Brasovan explains the different concerns.

Episiotomy, considered one of the most invasive measures in childbirth, and feared perhaps second only to having a caesarean section, still remains one of the most common surgical procedures experienced by women. As a UK midwife new to New Zealand, doing an episiotomy was something I was trained to avoid unless absolutely necessary. So, when my friend recently recounted her birth to me and told me how relieved she was to have had an episiotomy instead of "being allowed" to tear, I was taken aback, and felt myself silently questioning the kind of information she had been given to have reached such a conclusion. Was the practice in New Zealand radically different from what I was used to, or was this just an unusual case?

She had a straightforward pregnancy and had conscientiously prepared herself to do things "as naturally as possible." She had a spontaneous and, to her merit, drug-free labour, and was free of any intervention until her baby's head crowned. "And then the midwife did an episiotomy and my baby was born!" she said emphatically.

The midwife in me could not help but ask why exactly she had had the episiotomy. It was her fear of tearing. She had been terrified in her pregnancy of this: Thinking it would hurt and of sustaining a severe tear (like a friend of hers had). She said she had discussed her "choices" with her midwife antenatally, and during her labour, her midwife informed her that she may tear, and so she opted for an episiotomy. What followed her episiotomy was a postpartum haemorrhage and iron replacement therapy, regular pain analgesia for over three weeks because of the considerable perineal pain, and what she described as having "pulled" her stitches caring for her new baby. She had over a dozen sutures and after three weeks, was only now finding things more comfortable "down below." Her relief at not tearing was evident. But where was the evidence to say that the tear she may have incurred would have been worse than the weeks of recovery following this episiotomy? I thought it such a shame that here was a woman who had a completely normal pregnancy and labour, yet still ended up with an invasive surgical procedure. Her relief was based on the assumption that this procedure somehow saved her from a worse fate, when the evidence demonstrates the opposite. It was as if at the very last minute, trust in her body's ability to carry out this brilliant display of giving birth needed to be thwarted by a surgical procedure to "help get the baby out."

Episiotomies in New Zealand and beyond

Studies show that management styles and episiotomy rates vary from one practitioner to another. A recent study examining the worldwide rates of episiotomy concluded that there is considerable variation between countries, within countries' institutions, and within the same professional provider group.

In 1996, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that episiotomy rates for normal births should not exceed 10%. This was after attempts to address the previously high rates of episiotomy (more than 75% in many units), when liberal use of this procedure as a matter of routine dominated obstetric practices worldwide. An Australian study showed that women in private care were twice as likely to have an episiotomy.

Here in New Zealand, the national episiotomy rates are currently published as 12.1%, but when looking at separate units, the national rate of a tertiary unit is 17.1%, a secondary unit is 10.6%, and a primary unit is 4.7%. National Women's Hospital in Auckland has an episiotomy rate of 21.5%, and the New Zealand college of Midwives report a rate of 7.7% for midwives. Obstetricians will have higher episiotomy rates than midwives because they also perform instrumental deliveries. Because of the disparity found in these figures, one could argue that a woman's chance of getting an episiotomy is very much dependent on the setting and practitioner (LMC), rather than having any clear guidelines in place.

The New Zealand College of Midwives does not presently publish a consensus statement on the use of episiotomy in childbirth. It stands to reason then that it is important to discuss your LMC's philosophy and what they consider would be a clinical reason to recommend an episiotomy before your labour. This article will examine some of the current evidence available comparing episiotomy to spontaneous tearing.

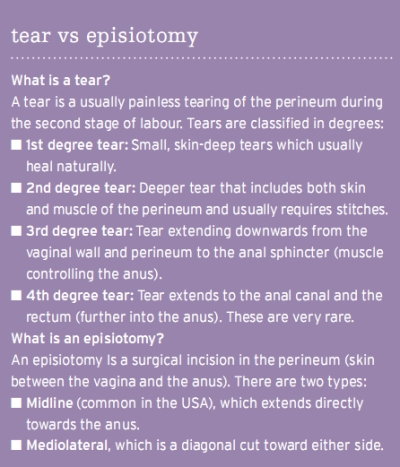

Sometimes, a cut is necessary

There are times when an episiotomy is necessary. And it can become a life-saving procedure, particularly in the case of foetal distress. In select clinical cases, an episiotomy is the better option, and women need to understand the reason an episiotomy is being recommended. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom recommends an episiotomy be performed only in the case of foetal distress or instrumental delivery, and should not be routinely offered to women who have previously had third- or fourth-degree tears. Some literature suggests other times when a practitioner may evaluate (with you) the need for an episiotomy, and these instances may include the case of shoulder dystocia, a particularly long second stage of labour, a rigid perineum, or maternal exhaustion, but these indications are more contentious and not necessarily as well supported by current evidence. The most important questions to ask in relation to an episiotomy are, "Am I okay? Is my baby okay?"

A tear down there

Is the case of performing an episiotomy to avoid a tear evidence-based? The answer in literature suggests an overwhelming "no." The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) conclude that it is not possible to predict or prevent third- or fourth-degree tears. There are, however, some factors that may indicate when a severe tear becomes more likely. These include a shoulder dystocia, a long second stage of labour, first vaginal birth, a large baby (over 4kg), and when labour is induced or assisted. If your baby is born with their hand by their face, this, too, may make tearing more likely.

Over 20 years of studies examining the effects of episiotomies have reached some important conclusions that recommend its use only in absolute clinical need. Some of these reasons are as follows:

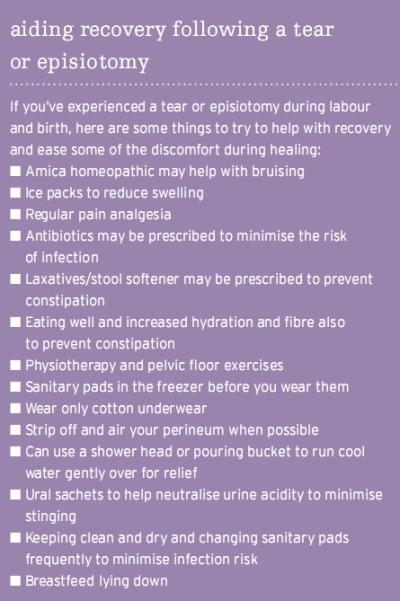

- Episiotomy is more likely to cause unnecessary perineal trauma, where many women end up having both a tear and an episiotomy that requires more suturing, longer recovery time, increased blood loss, and risk of infection.

- Episiotomy does not protect against urinary or faecal incontinence, anal sphincter damage, dyspareunia (painful intercourse), or perineal pain. This belief is completely unfounded in the literature, and episiotomies have actually been found to predispose to these types of conditions. Research has shown that deep tears are nearly exclusively extensions of episiotomies. This makes sense if you think about tearing a cloth: It's very resistant until you snip it!

- Episiotomy has been found to significantly weaken the pelvic floor function, and is associated with weaker pelvic floor strength postpartum compared with spontaneous tearing. This supports the contention that performing an episiotomy to "prevent" a tear actually contributes to a significant decline in pelvic floor function.

- Episiotomies are not easier to repair than tears, and are associated with significantly greater blood loss. Nor do they heal better. There is a risk of infection (also found in tears but don't usually go as deeply into the perineal muscles as an episiotomy).

- Episiotomies are not less painful and, in fact, may cause a lot more long-term problems with pain, which can affect sexual intercourse (severe tears can also impair this). The incidence of a third- or fourth-degree tear in a spontaneous vaginal delivery is 0.2-1.5%. Following an episiotomy, it becomes 4.3%.

Things to do to minimise the risk of perineal damage:

Antenatal pelvic floor function may partially determine perineal outcomes so exercises to strengthen your pelvic floor for delivery may be beneficial (see "Fitting in Fitness" article). A tighter pelvic floor means more control and slower descent, and gives baby support to flex its head and get into an optimal position. Equally, the degree of exercise plays an important role in pelvic floor recovery following childbirth.

Good nutrition and hydration will support skin elasticity. Vitamins C and E and bioflavonoids are important in maintaining tissue integrity. A study also showed that a high Body Mass Index (BMI) was associated with greater risk of tearing and episiotomy. Getting into shape before pregnancy and maintaining your well-being during pregnancy can have a positive effect on minimizing perineal damage.

Upright or lateral positions during labour and birth are associated with greater maternal comfort and less perineal injury. Lithotomy position and lying on your back increases the risk of episiotomy and tearing, as do epidurals. Women should be encouraged to choose their preferred position.

Doing prenatal yoga can help you to maintain flexibility, and some consider positions, such as the "open" position or practicing squatting to open the base of the body as wide as possible, help to pre-stretch prior to birth, but little research has evaluated the effectiveness to date.

"Hands-off" versus "hands-on" delivery management are methods used by practitioners during birth. Some will control the head, guard the perineum, and deliver the shoulders. Others will not touch a baby or perineum and will allow the birth to happen spontaneously. There seems no advantage of one over another in relation to minimising perineal damage, according to research available. Present evidence supports both management styles as valid approaches to birth, and different philosophies and training will underpin a practitioner's choice of styles.

Two studies indicate that perineal massage in the later weeks of pregnancy may help in preventing tears. Daily massage appears to have best effect. perineal massage in labour has shown no beneft but equally no harm. Studies are limited. This is the same as warm compresses in labour. Most studies compared coaching second-stage pushing (directed or Valsalva) with self-paced pushing, and showed an increased rate of intact perineums and greater pelvic floor function postnatally with self-paced than with directed pushing. Some consider the pain due to stretching the vulval orifice (the "burning ring of fire" pain) during crowning, which causes a lot of women to cry out, hold back, or pant, is actually acting like a "safety-valve" to protect the perineum by allowing slow, deliberate descent. So pushing using the pain as the messenger, rather than pushing through the pain, can enable women to tune into when to counter and when to ease back, thus breathing the baby out with less potential for trauma to result.

Some literature suggests water birth can minimise perineal damage, but other studies have found no significant differences. There is an argument, however, that water birth can minimise perineal injury in the sense that a woman can be more relaxed and more self-directed in her pushing, has less chance of an episiotomy, and can adopt a position of her choosing easier. It does appear that a reasonably comfortable mother, slow and controlled expulsion of the head, and shared responsibility for the outcome are all important factors in reducing trauma.

Don't shoot the messenger

In my own births (one water birth), it never crossed my mind to fear tearing. I knew you never felt it at the time (but you can surely feel an episiotomy if the timing isn't perfect!) and perhaps it was because I was a midwife, and had cared for so many women who'd had intact perineums, or small tears. Perhaps it was my understanding of the available evidence that really didn't provide me much of a "choice" in the matter - the alternative of opting for an episiotomy without sound clinical reason didn't measure up. It may have been because somewhere inside of me I believed that if I did tear, it was part of the process - and I believed in the ways to try to minimise this risk, so I birthed my babies in my own position, my own way, my own setting, and breathed them out rather than listening to someone telling me to push. With both my babies, I followed an instinctive need to touch their heads, which I do believe helped me to control the stretching with a slow crowning. And perhaps I just entered birth optimistically rather than with fear, and decided all I could do was trust and follow what my body would reveal to me in that experience. With both my babies I tore a little bit. Neither tear required any sutures.

Birthing is a rite of passage. Our bodies go with us on our journeys, and often it is through our bodies that we learn more about ourselves. I watch my four-year-old learning to ride her bike and I cringe sometimes with the anticipation of that fall she will most likely endure, and the scraped knees and possible scarring from the experience. In my efforts to protect her from the pain, do I prevent her from riding her bike? Is pain a negative thing to feel? Just like the tears I endured with the birth of my children (and the pain of childbirth!), the message behind it is one of growth, of learning, of joy and endurance of the human spirit. If pain is just the messenger, maybe we should think twice before we shoot it.

Paula Brasovan is a registered midwife, medical herbalist, holistic nutritional consultant and certified nutritional consultant. She is a busy mother and is well aware of the importance of being able to access reliable, accurate and current information about pregnancy and parenting. Paula's decision to serve as a midwife is due to her desire to enhance and educate people's awareness of themselves and the world in which they live.

AS FEATURED IN ISSUE 8 OF OHbaby! MAGAZINE. CHECK OUT OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE BELOW