The 3 stages of labour explained

OHbaby! expert obstetrician and gynaecologist Dr Celia Devenish outlines what to expect in the three stages of a “normal” birth process.

Most first-time mums will view the impending delivery of their baby with mixed feelings — excitement as well as trepidation. But in New Zealand we’re lucky that skilled midwives provide one-to-one support during labour and can respond to any problems that arise.

Every woman has access to a specialist’s care or advice for any difficulties when needed. Nevertheless, the prospect of labour onset inevitably causes concern for the baby’s wellbeing. There may also be a worry or tension that, despite preparations, you may not achieve your birth preference.

Keeping a positive attitude is best helped by the knowledge that you will have a support team and family or whanau around you who know you well and understand your preferences. Equally important is an understanding of the three basic stages of normal labour and what can be done to help your labour progress.

Women who are planning a vaginal birth after a previous Caesarean section (VBAC) can expect the same labour stages, but a close eye is kept on the foetal heart tracing or tones for reassurance, and on maternal recordings and progress for safety reasons. For those who have induced labours, once regular contractions have been established, it is expected that the active phase of the first stage, and the later stages, should continue as in a normal labour.

Pre-labour preparations

The body begins the practice of real labour for several days or even weeks before active labour begins. These practices can be occasional “Braxton Hicks” contractions or runs of contractions with back and pelvic discomfort.

All of these are reassuring and indicate that the body is getting ready. But it can be hard to differentiate between these practices and the real thing. Each woman experiences these preparatory changes in a different way. The important thing is to know when to contact your LMC who will discuss this with you in some detail.

Waters breaking is an important sign, of course, but this may not always be a big gush. Once the waters have broken there is a loss of the sterile barrier between normal vaginal micro-organisms and the baby within. Labour usually, but not always, follows membrane rupture. Your LMC can check this by examining you.

It is sensible to have a clear plan of who to contact and when. Also, of course, you will need to think about how you will travel to your chosen place for the birth, especially if there are other children to be cared for. With all this organised you can concentrate on your own needs in the first part of labour.

The first stage

During the first phase of this stage, the neck of the womb, also called the cervix, slowly thins and opens. This is a result of the uterine muscles getting progressively shorter with every contraction. It is often called the latent phase as not a lot of change is obvious. The baby’s head will engage during this stage if it has not already descended. As it is entering the pelvis, the head shapes to the birth canal within the pelvic cavity and gradually aligns in the best position to allow the baby to descend. Many women having their first baby will have their baby’s heads engaged (that is, the baby has “dropped” and is already pressing on their mother’s bladder) from 36 weeks gestation onwards.

Once the uterine contractions establish a rhythm of around one contraction every 10 minutes, the cervix starts to thin and open. The timing of this varies hugely. Keeping mobile, upright and active is very helpful, as gravity assists all stages of labour. Walking, even using stairs or just pottering around at home, resting as needed, are the best ways to wait out this phase.

Nourishment and fluids are also important to assist the normal physiology of labour because, as with any muscle exertion, hydration is very important.

The level of discomfort during this phase — until the cervix is 3-4cm open and soft — also varies widely. Backache, period-like abdominal pain and deep discomfort are experienced to various degrees. This process is all about preparation for the active part of the first stage and can vary from several hours to days or even a week or more. It is best to stay in comfortable, relaxing surroundings where possible until the active phase of the first stage of labour begins.

The stretch and pressure of the head on the cervix promotes the release of local hormones called prostaglandins which allow the cervix to soften and change as needed for labour to progress smoothly. The waters around the foetus may not break spontaneously, but can be ruptured artificially. This generally assists progress in labour and any blood or meconium staining is noted, as this can reflect on the baby’s wellbeing.

The “active” phase of the first stage has a more predictable time frame. It usually lasts eight to 11 hours. During this phase the cervix actively dilates. The rate of dilation in first labours is around 1-2cm an hour and generally faster in subsequent labours.

Once the rhythm of the uterus has established three contractions in 10 minutes, the baby can begin to descend and rotate as the cervix eventually achieves full dilation.

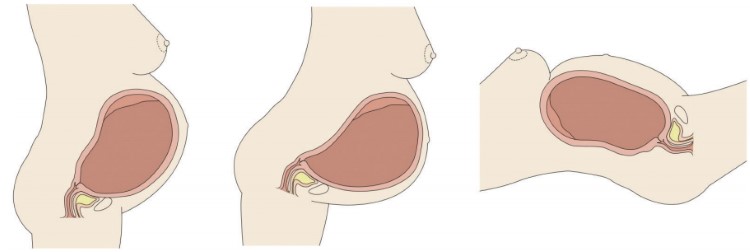

POSITIONS OF UTERUS WHILE MOTHER IS IN DIFFERENT POSITIONS

| Standing: gravity helps contractions a lot |

Leaning forward: gravity helps contractions a lot |

Lying down: gravity helps contractions a little |

Again, remaining mobile where possible and leaning forward from a standing or kneeling position allows gravity to maximise the work the uterus is doing (see diagram above). Regular breathing for this stage of labour, as practised in antenatal classes, allows relaxation at the same time as physical work.

Reducing tension in as many ways as possible between contractions allows the uterus to work most efficiently. Your LMC and support team are important at this stage to reassure you. Emptying your bladder regularly is also important throughout labour.

To assess how the labour is going, you’re likely to have regular vaginal assessments of cervical dilation and the position of the baby’s head. Equally baby’s and mother’s wellbeing need monitoring regularly to ensure adequate hydration, normal blood pressure temperature and pulse rate and reassuring foetal heart sounds or CTG tracing. (CTG is an electrical pick-up and printout of the baby’s heart beat).

There are a range of options for pain relief in labour. Water, breathing techniques and massage are low-key therapies which assist progress through the first stage. Warm compresses and a TENS machine can also be used to good effect.

Music and creation of a preferred ambience may assist too, but above all, it is the feeling of support that enables a woman to settle into labour and allows the birth process to sweep through her.

Entonox (laughing gas or nitrous oxide) is useful to many women to tide them over the most intense contractions.

An epidural may be advised because of raised blood pressure, foetal position or difficult progress. The advantages of an epidural in such situations are obvious, as the epidural allows the woman’s body to relax and enable labour to happen.

Some women elect to have an epidural which offers a pain-free labour. Opiates can also be useful for some women. Each labour and every woman is different, so choices should be made according to individual needs and circumstances. Your LMC will assist and advise you in these choices.

The second stage

Transition to the second stage can be announced by a change in the contractions which may become more intense, multi-peaked and occasionally, temporarily overwhelming. It is important not to push until the cervix has completely gone to avoid tearing.

Progress of labour is often recorded on a partogram which allows both carer and mum to see cervical dilation and the head’s descent in a visual graphic over time.

A small number of women, even in their first labour, can experience very fast, relatively painless labours which last just a few hours. The risk is they may deliver before their planned venue! This is not common, but usually makes the news! The second stage is when the baby actually passes through the pelvis to the perineum so that birth can occur.

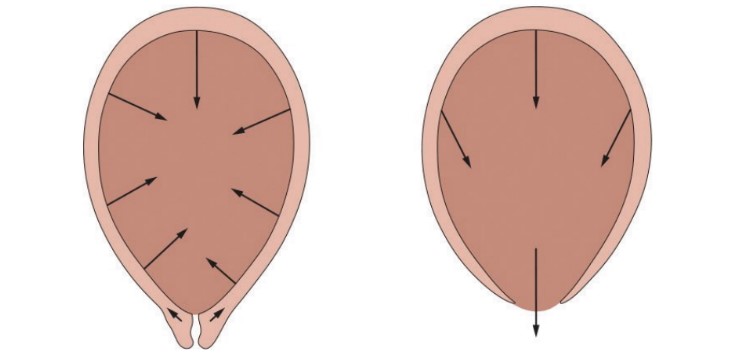

FORCES EXERTED BY THE UTERINE MUSCLES DURING LABOUR

| First stage | Second stage |

Once the cervix is fully dilated (around 10cm) the uterine contractions change to expulsive contractions propelling the foetus to the outside world (see illustration above).

The head is usually the largest part of a baby. Should the shoulders be wide then the passage of the baby can be held up, and special manoeuvres may be needed to assist delivery.

The second stage usually takes around 30-60 minutes. Women generally find the urge to push is quite involuntary. LMCs and your support team will guide you through this. While an epidural may slow this process down, waiting a while for sensation to return before pushing is fine.

Women are encouraged to actively push using contractions to their best advantage. This is achieved by taking in a full breath in and holding it as long as possible while pushing throughout the contraction. Women are encouraged to “push through the pain”. Contractions last 60-90 seconds with complete relaxation and rest in between times to allow efficient progress. Sips of liquid, ice and cold compresses all help.

Sitting upright, squatting or kneeling on all fours can assist the baby’s descent. Which position you choose is really about what feels best at the time. It is a good idea to keep an open mind and try what appeals most.

Once the head has travelled “around the angle” of the birth canal the scalp and hair can be seen. The birth is now imminent.

At this point the baby’s head distends the skin and stretches the muscles of the perineum. Your LMC may ask you to stop pushing but to pant instead. This part is called crowning. The aim is to minimise damage to the perineum as it thins down.

The baby’s head partially rotates after release from the perineum, at the same time the shoulders and trunk are entering the pelvis and passing along the birth canal curve, until the child is born.

From time to time, in order to avoid tears to the anal sphincter, a small cut or episiotomy may be made to relieve excessive pressure on the perineum. Any spontaneous tears or cuts are repaired after the birth is completed.

The third stage

The third stage lasts from the birth of the baby to delivery of the placenta. The placenta is soft and its separation and delivery takes around 30-60 minutes. During this last stage your baby will be a welcome sight and hopefully you can have a cuddle.

It is important that the placenta is delivered complete to avoid complications, and the placenta is checked for this.

Some women experience significant after pains once the placenta is delivered. This is normal and reassuring, as it means the uterus is contracting down to prevent bleeding from the site where the placenta was attached.

Active management of this third stage is recommended. This entails an intra-muscular injection of syntocinon to the mother at the baby’s birth. Active management halves the rate of excessive blood loss known as a post-partum haemorrhage (more than 600ml) and the use of syntocinon is very safe. It should be recognised that in Third World and other countries lacking such basic resources, excessive bleeding is the most common cause of maternal death and ill health.

All these stages can sound like a lot to accomplish! However, with good support, surroundings in which you feel safe, and a basic understanding of the stages of labour, you will have the best outcome possible, for your particular labour.

After all the work, there is the miracle of motherhood. This joy supplants many of the memories of labour itself and of the supreme efforts made over the preceding hours. Your newborn photographs will confirm this!

Dr Celia Devenish is the clinical senior lecturer at the Dunedin School of Medicine and a practising obstetrician and gynaecologist. She is passionate about maternity care and is currently researching the reasons behind placental dysfunction and untimely births, as well as the best delivery methods.

Illustrations supplied courtesy of Bridget Williams Books and taken from The New Zealand Pregnancy Book.

main photo: @jeswfromtexas via Twenty20

AS FEATURED IN ISSUE 24 OF OHbaby! MAGAZINE. CHECK OUT OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE BELOW