Toddler talk

Trying to find out what your toddler is really thinking can be difficult. Dr Melanie Woodfield explains some simple strategies that you can use to open up the lines of communication.

Having a real conversation with a child of any age can be a very tricky task. Most of us can manage the "How many sandwiches would you like for lunch?" conversation, but how would we fare with "Daddy doesn't live here anymore"? Toddlers can be a tricky group to chat with too - short attention spans, coupled with limited language skills, and a difficulty grasping abstract concepts, mean that we need to think very carefully about how to say what we want to say to avoid a misunderstanding. Talking to toddlers about the "deeper" issues is something we need to do as parents. Things like checking whether they are happy at kindy, or why they cry every time they see Grandma, or preparing for a discussion where you need to explain why daddy won't be coming home - these are all things that we may grapple with. So, rather than an article on how to get compliance from your children, this is an article about how to talk with your child in a way that encourages them to say more, makes them feel valued and listened to, and gives you an insight into their world.

My psychology training gave me a good basis for the theory behind what works when talking to children - information about language and social development and interpersonal skills. However, most of what I know has come from talking with children in my professional capacity, and discovering which factors help encourage children to talk, and which factors don't. Most of us know, for example, that asking an adolescent "How's school?" is likely to elicit one of two responses "good", or "fine". Are you curious about which factors will improve your chances of having an 'in-depth" chat with your preschooler? Read on! As with most tips, they won't work with every child, but should give you a good basis from which to begin.

WHERE

First things first - where you choose to hold your conversation is important. Some children will feel at ease in a setting where they don't have to engage in direct eye contact, such as travelling in the car, and others prefer having a distraction such as drawing while talking. Be aware that the younger the child, the less likely it is that they can multi-task - drawing while talking may be a challenge, and either the drawing or the conversation might suffer!

Having said that, coming alongside your child while they're engaged in a task can be a nice way to engage with them. Try commenting on their activity, in a way that invites their response. For example, "I can see you're using lots of green paint on your painting. Tell me about what you're doing." Sometimes we don't even need to invite the child to respond by using the "tell me…" statement - a technique such as using the third person and "wondering" can be very effective, for example, "I can see Sammy is really working hard on his painting. I wonder if he's enjoying it?" A child may not respond to this, but if they do, their comments are likely to be more elaborate than the response to an alternative question such as "Are you enjoying it? Do be aware, however, that use of the third person can be confusing to very young children.

WHEN

Also be careful of your timing - most children will be wary of an adult who is trying to be very chatty and friendly immediately after they've been very grumpy! Choose a time when you and your child have some alone-time - settling to bed can be a nice time to talk, but not necessarily if you're planning to delve into emotionally charged stuff that could then become the stuff of nightmares. Other nice times could be travelling in the car, walking home from kindy, when other children are napping, or while you're preparing dinner and your child is nearby.

HOW

Firstly, it's important to be aware of how you're coming across to your child. If you're madly flustering around the kitchen, your child may get the impression you're not interested in what they have to say. Beware the adult tendency to cross arms and legs, or look at your watch. Children are pretty perceptive of these non-verbal cues that you're not interested. Also, in general, children tend to "protect" their audience from emotional distress. In other words, if they start to share something with you and you appear too shocked or angry, some children will simply stop talking or change the subject.

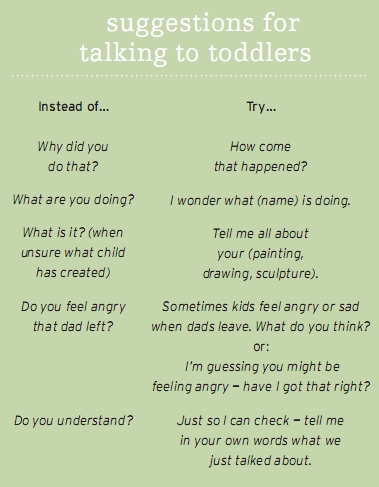

Thankfully, children are generally very forgiving of sentences or questions that don't make a lot of grammatical sense. For example, I'll often ask children "what's that about?" when I don't understand something, or want them to elaborate. Instead of looking confused, they usually oblige, and proceed to explain in more detail. Similarly, instead of asking "why?" I'll often ask "how come?", and, for some reason, children seem to like this. These subtle changes in the wording of phrases can make a big difference to how children respond. Refraining from using "value" words such as "good" and "bad" can be a useful touch too - try "OK" and "not OK" instead.

If you need to share important information, it's often useful to check the child's understanding of the discussion you've had. Younger children, especially, will almost always say "yes" when asked "do you understand?" - particularly if the adult asking is looking rather serious. Children are typically very aware of the subconscious emotional power imbalance that exists in an adult-child relationship. Most young children are reluctant to rock the boat, and possibly invite a reprimand, so will indicate that they have understood, when in fact they haven't.

An example I'll never forget hails from my days as a conscientious psychology trainee interviewing young children. I remember asking a young child directly "do you have any worries or troubles that you want to talk about?" and the child responding with an immediate "nope." A few beats later, I thought to ask "Do you know what worries and troubles are?" to which the child replied with an emphatic "no."

Bear in mind that abstract concepts such as "worries" are very difficult for young children to conceptualise. Children around 5-6 years onwards may be OK, but proceed with caution! For preschool children, it's usually best to stick with three basic emotions, such as happy, sad and angry. What I've found helpful is to get the child to draw a happy face, a sad face and an angry face on a piece of paper, then show me that particular expression on their own face. I'll usually then go on to ask them to tell me about a time when they had a happy face, or a sad face, etc. You can then use the faces to start a conversation about particular experiences or settings. For example, "which face do you have on when you're going to kindy…? (child chooses)… tell me all about that", but (and I can't emphasise this enough!), don't read too much into the child's response in isolation. Just because your child chose a "sad" face to represent her time at Daddy's place last weekend doesn't mean that she dislikes her father - it could simply mean that Daddy wouldn't buy her a Happy Meal.

Metaphors and analogies, carefully used, can also be very helpful. For example, I've explained difficult situations to children in the past using teddy bears. "Even though Mummy Bear and Daddy Bear loved Baby Bear very, very much, they found it really hard to live together…"

I hope these tips have been helpful in providing some creative ways to approach the challenging task of having a "deep and meaningful" with your toddler. This is merely the tip of the iceberg, and each child is different. Be encouraged that if the tips don't work for you, it will get easier to talk with your child as they age. Get in quick though - it starts to go downhill again in adolescence!

Dr Melanie Woodfield is a child and adolescent clinical psychologist in Auckland.