How can we raise a creative child?

Want to raise a creative child? Psychologist Dr Melanie Woodfield explains how to stimulate a toddler's imagination.

Kids are naturally imaginative. It's their curiosity about the world, lateral thinking and unconventional problem-solving that fuels their mental, social and emotional growth. As parents, we can support children to think freely and encourage their imagination. It's worth the effort - children who have been supported to think creatively often grow into creative adults. Adults who are creative, innovative and entrepreneurial are highly valued by society: they might be your local advertising executive, artist or musician, but they may also be the imaginative scientist who finds the cure for cancer or discovers an energy source that results in humans living on Mars.

Creative kids usually come across as confident and self-assured. They're not afraid to give a challenging problem a go, as they know they have a variety of mental tools to do so. Giving things a go and looking at all the possible solutions means they're more likely to succeed. And we all want kids to succeed, whether they succeed academically, socially or simply succeed in achieving a happy and healthy life. So, bring on the imagination!

Why now?

Children's brains develop faster in the first three years of their life than at any other time. Wonderful organisations such as the Brainwave Trust (www.brainwave.org.nz) have made it their mission to share research showing children are born with the "hardware" for their brain computers but most of the "software" forms in the first three years of their life. Put simply, connections are formed between brain cells each time a baby or toddler has a new experience. These connections are strengthened if the experience repeatedly. We're all (hopefully!) doing the basics of providing a loving, nurturing and supportive environment, but we can also encourage our children to think laterally, creatively and imaginatively from an early age.

At a basic level, we can provide children with the fuel to think freely. I'm not talking expensive pencils or yoga classes but simply providing a metaphorical platform by starting discussions, initiating activities or simply wondering aloud about something.

Go on, baby, express yourself!

First up, at the risk of preaching to the choir, I'll take a moment to remind you of the importance of being okay with the choices your child makes. Young Stanley may find fairy wings and pink plastic pumps irresistible and that's okay. Darling Susan might want to wear gumboots with her shorts and singlet and that's okay. Of course we need to keep children safe, and educate them about common social practices ("Darling, most people wear only one pair of undies…"), but, especially in the preschool years, try to allow your child to express herself. The decisions they make at this age are unlikely to represent enduring social, sexual or fashion inclinations. They are more likely to be a product of their natural urge to experiment.

But if you struggle to live in a fully child-led environment, you're not alone. Most of us need to retain some level of control, while still allowing our children to express themselves and encouraging heir imagination. There is a happy middle ground that involves coming up with fair and negotiable limits. Try to allow your child to have choices as often as possible throughout the day, but offer them a choice of two or three options that also work for you and other family members. Most children respond well to a choice between, say, whether to draw or paint, or whether to wear the blue jandals or the pink ones.

Some experts suggest that to truly allow a child to express her creativity and imagination she ought to be allowed to create mess. Now, if you're anything like me, hearing the "m" word results in an involuntary curling of toes. My view is that, yes, children need space to create, and creation often involves mess. But, this has to fit within the family - both physically within the house and within the value system of the family. I aim for compromise- yes the kids can make mess but their mess needs to stay in the bedroom or on the deck. We can negotiate other more temporary "creative spaces" as the urge strikes, but these spots disappear at the end of the day.

I'm also a big fan of creativity that is expressed in a way that meets everyone's needs. I love the example of giving a child a big soapy bucket of water and a big fat paintbrush and inviting them to "paint" the windows and the house. They love it, and can be creative to their heart's content, and I love it because it washes my windows. Chalk and washable crayons also work well.

Stand back, Mama

Many of us struggle with the urge to jump in and "fix" things when children are experimenting. It's easy enough to setup an activity or conversation that can encourage a child to use her imagination. It's also easy to shut it down by interfering. In order to promote creative thinking and imagination explosions, try to allow your child to make her own mistakes. It's a cliché, but mistakes really do provide us with a new opportunity to think about things in a different way. It's important to try not to do it for your child, even when she is impatient or keeps asking you to. If you're confident that she can find a solution, tell her so, and provide as little support as she can cope with.

Lev Vygotsky, a big name in psychology and education, inspired a term called "scaffolding" to describe how adults can best support children to learn. The idea is that we provide a structure or platform for the learning to occur (much in the way that a scaffold allows a building to be constructed) and, as the child engages in the task (the building takes shape), the scaffold can be gradually removed, until the child is leading or guiding the activity.

Again, it's a cliché, but it can be helpful to see yourself as a coach and your child as the player. She needs to play her own game but you're there to offer encouragement and validation ("that looks like a really hard problem to solve, I really like how you're taking your time and trying different things") and support.

Ultimately, independence can be the road to problem-solving, which promotes creativity and imagination.

Stimulate the senses

There are many opportunities to spark imagination, both child-led and adult-led. A child-led scenario might look like this: Darling son or daughter presents a Michelangelo-like work of art, while bursting with pride. We're delighted that he sat so quietly for so long to compose this… this… masterpiece. Only one problem. He's desperate for our approval and comment. But the piece of art doesn't look like anything we've seen before. We have no idea what it is.

Now of course it's okay to ask your child directly what it is he's drawn. But you may then find yourself with a crestfallen toddler who, in his mind at least, has drawn a very obvious elephant. Instead, you could try stimulating his verbal skills and inviting him to tell you all about his drawing. Remember to validate ("I can see you've worked really hard!"), and maybe throw in some descriptive praise for good measure ("I like how you've used gold stars on top of the yellow sun").While the child has been the catalyst for that interaction, you as a parent have a role to play in leading the opportunities. Believe it or not, even the most stimulating DVD or television programme will not encourage imagination as effectively as a discussion, a reading, a hands-on activity or an experience. Don't get me wrong, television has its place (I sometimes count the hours until 6pm, after dinner, when my children are allowed to watch it), but many experts recommend that it be used as a treat rather than an everyday activity. It's interesting too that, paradoxically, complex "developmental" toys (which are usually hideously expensive) can stifle imaginative play. Have you noticed the recent trend for getting back to basics with toys? They might be good-quality wooden blocks and trucks or baby blankets which simply have tags hanging off them. Critics of the complex toys have argued that, when all a child needs to do is press a button and watch, he is less likely to remain engaged or use it in different (perhaps more creative or imaginative) ways. If presented with a simple but versatile basic toy, he is forced to think of different ways to use it. That cardboard tube becomes a didgeridoo, a telescope, a scoop, a stilt or a microphone.

Parents often find that it's difficult to reintroduce basic toys if kids are used to the complex options. Kids can get frustrated that the block doesn't DO anything. It might help to start slowly, and supportively scaffold (as per Vygotsky).

Now of course children are usefully exposed to technology in the preschool years - for most, it's an advantage to at least be familiar with the bells and whistles. But, put simply, variety is the spice of life.

School for thought

I don't know about you, but when I think of a student of philosophy I tend to think of a slightly dishevelled lanky man in cords and a patterned jumper. He is probably carrying a stack of books and definitely gazing thoughtfully up at the sky. Well, this image is in for a shake-up, with the advent of Philosophy for Children, or P4C.

Ideally, preschools, daycares and kindergartens do offer children the chance to stretch their imagination muscles. Some settings are that way inclined philosophically anyway - think Steiner and Montessori - and provide lots of lovely unstructured play where children can explore their own interests.

Dr Vanya Kovach, who co-ordinates Philosophy for Children New Zealand, says P4C in preschools here is still in the very early stages but is probably going on informally in many early childhood settings.

Classes are led by teachers specially trained in teaching philosophy to children, but several of the techniques and strategies can easily be adapted at home.

It could be worth a try. Practitioners of philosophy in schools report higher IQ scores as a result of lessons in philosophical thinking for pupils.

Home work

There are plenty of opportunities to engage your little one in a debate on life's big issues.

A never-ending story is a fun idea with a preschooler… "Once upon a time there was a big bear and he lived..." then get your child to pick up the story… "at the zoo and his favourite thing to eat was…" etc.

Also, try 20 questions at the dinner table. Print them out, cut them up and put them in a jar or hat for everyone to pick out. Here are some suggestions to get you going:

- If you could have picked your own name, what would it be? Why?

- What animal would you be? Why?

- If you were given three wishes, what would you wish for?

- What would you rather be: an All Black, the Prime Minister, a movie star or a famous explorer? Why?

- What are the three best things about our family?

- If you were to have a weird or unusual pet, what would it be? Why?

- What makes a good friend?

You'll notice in those examples there are lots of "whys". This question seems to provide more of a platform for discussion than the usual what/where/when/who questions. The younger the child, the more he may struggle to answer the "why" questions (although children are very good at asking why). You could try re-phrasing it as "how come?" and see if that helps.

A good way of starting a discussion is to read a book together and talk about it afterwards. Go to www.teachingchildrenphilosophy.org/wiki/Category:Book_Modules for reading ideas and ways to start discussions.

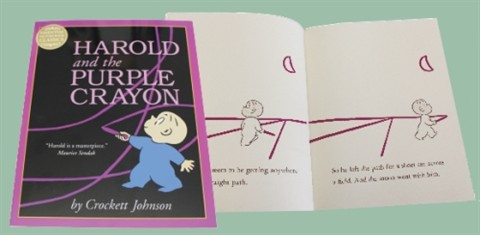

Harold and the Purple Crayon by Crockett Johnson is a good example of a book that can stimulate discussion. Harold goes for a walk at night but finds that there is nothing to walk on, no moon, and nothing is real except Harold and his crayon. He goes on to draw his surroundings, but what's really real? Here's an example of questions to ask your child:

- If Harold is drawing his world why does it take him so long to find his window?

- Do you think Harold could get lost in the world he is drawing?

- What does it mean to be lost?

- What would you do if you were lost?

Fascinating, challenging discussions can also start very simply. I've worked with children for many years and I often "wonder aloud" which works very well. I use it as a therapeutic tool, for example, "I wonder why Daddy said that to Mummy?", "I wonder where that anger was hiding?". But it can work well as a starter for discussions with your child at home. You might be chopping the carrots for dinner and drop into the conversation, "I wonder why cats stay close to home?" or "I wonder what makes the noise when thunder happens?". The trick is to "wonder", and then say nothing. Allow your child to suggest a theory or a thought. Sometimes she won't, especially if she's not used to it or thinks you're testing her, but usually she'll come up with something remarkably insightful.

Encouraging imagination is about providing opportunities for imaginative play, offering lots of choices, not jumping in and fixing problems and providing scaffolding for learning. Maybe it's time for us to adjust our perception of a philosophy student from a dowdy, cord-wearing young man to a wee toddler wearing undies on her head and a huge smile.

Useful books and websites

* Thinking About Picture Books by Anne Maree Olley

* The Lion In the Meadow by Margaret Mahy

* Hemi's Pet by Joan de Hamel

* It's Not Fair by Anita Harper

* www.babycentre.co.uk/toddler/development/stimulating/imagination

* www.p4c.org.nz

Dr Melanie Woodfield is a child and adolescent clinical psychologist and a mother of two preschool boys. She struggles to follow her own advice about allowing mess in the house and not "fixing" things.

AS FEATURED IN ISSUE 18 OF OHbaby! MAGAZINE. CHECK OUT OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE BELOW