Why we need to banish the term 'terrible twos'

Who are you calling terrible?

Are you expecting too much from your toddler? Take a deep breath and read Miriam McCaleb's words of wisdom on how to parent a willful two year old.

What gives, New Zealand? What makes us think it's acceptable to label two year olds as "terrible"? "The Terrible Twos" is a common phrase used to describe our divine children as they negotiate the rocky path of toddlerhood. Just when toddlers need their adults to be at our most compassionate, understanding and helpful, we turn on them with our language and expectations. Within their earshot, these groovy toddlers are described as "terrible".

If I knew I was being described as a "Tragic Thirty-something" rapidly approaching my "Foul Forties", I would be highly likely to lay my most awful behaviour on you. Really, you wanna see terrible? I'll give you tragic! You ain't seen foul like I can deliver it...

We've certainly moved on from thinking it's okay to use such terms when describing gender, ethnicity or ability. So why is it socially acceptable for two year olds?

Rise up, dear readers, and join me in a campaign to say "NO!" to using this unfortunate moniker. Yes, friends, beware the power of the self-fulfilling prophecy.

Bye bye baby, hello toddler

Let's explore some of the developmental tasks of children as they near the age of two, and how we as adults need to adjust our expectations. After all, when we know what is going on for children during toddlerhood, we have no need to label their behaviour "terrible".

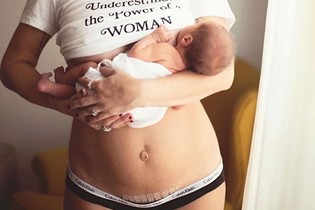

Toddlerhood can emerge as a shock to many parents. You've adjusted to the needs of infancy, you have been brave and giving as you negotiated sleepless nights, sore boobs, and the constant aroma of baby vomit. But along with the challenges, you've enjoyed the rewards of parenting a baby: the admiring gazes of folks on the street, the convenience of the non-mobile infant (still in the same spot where you left him, 10 minutes later!) and the glorious baby grins and giggles. Seemingly all of a sudden, this portable and somewhat malleable baby is replaced by a toddler, determined to practise his newfound walking (running, and climbing) skills, a toddler with his own ideas about where to go next and what he would rather be doing, wearing or eating. This shift must be met with a shift in your skills, or conflict will arise.

Dr Ron Lally, one of the founders of the Programme for Infant/Toddler Care (www.pitc.org), a research-based training organisation in California, talks about the tension that occurs when adults continue using the same skills that were successful in caring for a young baby when they're engaged with an older infant or toddler.

He explains that the main developmental task of a very young infant is to experience security, and that the ultimate caregiving style for a very young infant is modelled on a warm, bosomy grandmother. Calm, gentle, sensitive love delivered by an attuned and nurturing adult with tons of time to snuggle. Perfect!

But as that little baby grows into a mobile infant, the envelope of the cosy embrace becomes more of a part-time residence. The main developmental task of the mobile infant is exploration, and a child of this age (who has made the cognitive leap that "Mummy ends and I begin") has a ton of work to do in figuring out how his body works. He must learn to roll, commando-crawl, rock on hands and knees, pick things up with a pincer grasp, stand up, walk and climb. Huge work!

Step up, coach

Now that the mobile infant has started to walk, he is, by definition, a toddler. And toddlers have a whole new world to negotiate. They've mastered much of their physical work, and they're moving into the complex world of understanding relationships, emotions and identity. ("Me! Mine! I do it!") This learning is profound and important, and Dr Lally uses the analogy of a coach to describe the type of skill set that will serve a toddler well.

The coach is encouraging, clear and patient. The coach recognises that some skills will need to be practised over and again, without becoming frustrated. A skilled coach won't become angry or take it personally when they receive messages of, "I need your help. No, go away! I can do this on my own! Actually, hey, I really do need your help!", recognising that the need for support ebbs and flows when negotiating new skills - sometimes within moments.

No need to get mad about it - it's not naughtiness or willfulness, it's just how it is. Sue Gerhardt repeats this language in her excellent book Why Love Matters. She talks about the role of a skilled adult as an "emotion coach". Our toddlers need us to identify what they seem to be experiencing, to weave it with some empathy, and to avoid judgement of their emotion.

A threatening toddler storm in the supermarket checkout can be responded to with something like: "Oh, I know! All those chocolates look so interesting and it's hard when you can't have what you want, eh? Looks like you're mad about that! Oh well ... sorry, babe, no chocolate today."

This is quite a different message to, "Stop being silly. You don't need chocolate. Stop it!"

The limit is the same (I'm not buying a chocolate bar), but while the first response acknowledges that human desires and emotions are normal (and let's be honest, who's not tempted by the beautifully wrapped treats?), the second serves to add an unhelpful layer of shame to the mix (it's silly to feel like that). When we are honest with ourselves, we realise that it's entirely reasonable to feel discomfort when faced with the yearning for something desirable that we cannot have.

New car, anyone? Coveting another pair of impractical shoes or beautiful handbag? Yes, it's hard when we can't have what we want.

Local parent educator and university lecturer Nathan Mikaere-Wallis has another terrific analogy when talking about supporting children through this time. He talks about a child's need for an emotional apprenticeship. Just as the master mechanic wouldn't mock the junior for not yet knowing how to manage a blown carburetter, wise adults know we must share our experiences, to avoid abandoning children in the complex world of emotion.

Recipe for brain development

Exploring the work of Dr Bruce Perry, a Texas-based neuroscientist, author and child psychiatrist, gives us another lens through which to view this idea. Dr Perry developed what's known as the neuro-sequential model, a fantastic tool for understanding the way our brains develop. The neuro-sequential model demonstrates that toddlers are working with an incomplete brain. Their brains have a way to go before being totally organised. Is it any wonder they need our help?

This model teaches us a hierarchical nature of brain growth and function. Dr Perry uses the analogy of a layer cake: The bottom layer must be firm and cooked so other layers can rest upon it.

We now know that our brain uses a foundation of simple functions and later develops more complex functions. The first region of our brain to develop is the brain stem, focusing on survival functions, for example: breathing.

Next, the neuro-sequential model teaches us that toddlers do huge work to develop control over their bodies, as they wire up a region known as their mid-brain. Then, the "layer" of the limbic system is developed, and this is the home of emotion.

Anyone hanging out with toddlers will recognise that they often feel deep emotions, and they move from one to another for reasons that may seem illogical to adults. Most grown-ups have access to a region of the brain known as the cortex, which enables logic to override an emotional response. Research indicates we don't fully wire up our cortexes until we're in our mid-20s. So, to expect a two year old to "calm down" just because you say so is unreasonable.

Toddlers have an emotional brain, but they don't yet have a logical brain. Robust cortical growth happens most readily when it rests upon a strong foundation. This can't happen when the "layers" of the "cake" that sit underneath have raw cake batter in the middle.

It is arguable, then, that the best way to ensure a healthy wiring (and perfect bake time) for the limbic system is to engage emotionally with toddlers as they do the work of learning about feelings.

Imagine your 20-month-old wants to wear the green T-shirt and it's wet on the washing line. He's disappointed, maybe sad. Perhaps a tantrum is looming. While it's great if you take the time to talk with him about the wet fabric and the fact that he'll get cold if he wears it now, he will not be able to hear your logical messages and explanations while he's in the midst of his emotional reaction.

Instead, start with his emotion. "Oh, I can see your face looking really sad about that. Are you disappointed about the T-shirt being wet? Because you really love that T-shirt, don't you? But do you know what, honey? It's all wet! It was dirty, so I washed it, and now it has to get dry before you can wear it again."

See - all those logical explanations are in there too, but we must begin by allowing, acknowledging and explaining the emotion. Over time, children become more skilled at recognising the emotions that pass like clouds across their consciousness ("Yes, I'm angry!"). Knowing what they are, as well as having been coached about how to manage them, is essential in learning to regulate them - to calm oneself down.

Understanding tantrums

Speaking of regulating emotions, let's take a moment to talk specifically about tantrums. Tantrums are usually a result of a child not having yet learned to deal with their powerful emotions in more of a socially acceptable way. They are not usually about naughtiness or manipulation - remember, these children don't yet have much of a logical brain, so they're not able to plan, plot or control their parents.

Most tantrums are what author and child psychotherapist Margot Sunderland calls a "distress tantrum", and these children should be thought of as having the words "I need to be soothed" or "Help me to handle this" printed across their beings. These children need empathy, language to describe their feelings and perhaps some distraction.

The minority of tantrums are described by Sunderland in The Science of Parenting, as "Little Nero" tantrums. A child having a Little Nero tantrum is usually older, there are no tears or stress chemicals in his brain and body. Only a minority of tantrums are about manipulation. This is the child who needs clear limits and a calm, firm parent.

Which brings us to the final point. In order to be the sort of parent our children need us to be, we must strive for calm, warm, consistent parenting. This is very hard to do when we are stressed ourselves. Our buttons are pushed much more easily when we're tired, when we haven't learned to process our own emotions, or if we just need a snack.

So just as you're practising kindness and acceptance of those toddlers (the Terrific, Tantalising Toddlerific Twos), practise a little kindness and acceptance of yourself, too.

Miriam McCaleb has been working with children for 20 years. She reckons the coolest among them are toddlers. The last decade has seen Miriam concentrate on teaching the adults in children's lives (who are also cool) and in caring for her whanau (the best of the lot!). She works with the Brainwave Trust, blogs at http://www.baby.geek.nzand this February delightedly welcomed a new baby.

AS FEATURED IN ISSUE 17 OF OHbaby! MAGAZINE. CHECK OUT OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE BELOW